Civil War Comes to Arlington

In 1858 Thomas F. Perley constructed a residence on a large parcel of land along the river at Empire Point. A decade later he sold the property, called "Perley Place," to a prominent Jacksonville banker. The house later burned, but a wine cellar, dug into the bluff at the river and connected to the main house by a tunnel, survives. It is one of Jacksonville's rare ante-bellum structures.

The Federal occupation of Jacksonville depended

upon safe navigation of the St. Johns River by Union naval forces. In September,

1862, a squadron of Federal gunboats began an assault against a strong

Confederate position atop the St. Johns Bluff, which commanded the water

below. Landing operations began October 1 when a force of 1,500 Federal

troops landed on the south bank of the river below the bluffs and advanced

upon the Confederates atop the bluff. The outmanned Confederates fled and

soon the Stars and Stripes rose over the bluff. The engagement at St. Johns

Bluff permitted Union forces to control the river and East Florida for

the remainder of the war.

Civil War and Reconstruction (1861-1877)

Jacksonville was the site of significant activity

during the Civil War. Among the first of the important Southern ports surrendered

to the Union, it was occupied periodically throughout the war by Federal

troops. The first Federal occupation of Jacksonville occurred on March

12, 1862. At that time, Confederate troops stationed there retired to the

vicinity of Baldwin. On April 8 the Federals moved on, leaving many citizens

who had expressed oaths of loyalty to the Union undefended against their

returning Confederate neighbors. A second occupation lasted four days in

October, 1862, and a third for nineteen days in March, 1863. The third

occupation brought the uncommon sight of black troops in Jacksonville.

The

fourth Federal occupation began on February 7, 1864, when some 7.000 Union

troops were assembled for an assault on the Florida countryside. Repulsed

by Confederate defenders at Olustee, near Lake City, the Federal troops

retreated to Jacksonville, where they remained for the duration of the

war.

Though a slave owner himself, Sammis ardently

supported the Union cause. In 1860 he quit the lumber business and moved

to Baldwin, Florida, about twenty-five miles west of downtown Jacksonville.

He retained the property at Arlington Bluff, however. In the Spring of

1862 Sammis returned to Jacksonville to help set up a Florida government

opposed to secession. When the Confederates re-occupied the city he fled

to New York. There, in the summer of 1862, at a meeting of Florida Unionists

he met Lyman Stickney, a Vermont native, who had tried before the war to

promote new agricultural settlements in Florida. With Stickney's help,

Sammis secured an appointment to the Direct Tax Commission, created to

carry out the seizure and sale of lands in Florida held by rebeIs who had

failed to pay their taxes. Another member of the Commission was Harrison

Reed, a Wisconsin newspaper editor who after the war became the Reconstruction

governor of Florida. Sammis resigned from the Direct Tax Commission in

1863 after a dispute with Stickney and in February, 1864, upon the reoccupation

of Jacksonville by Union troops, returned to the city. He arrived with

a ship load of goods and set up business with Thomas S. Ellis, a Unionist

merchant in St. Augustine before the war. Two sons of Sammis, Edmund and

Egbert, worked with him in the store.

John Sammis apparently retired from Florida

politics after the war. In 1868 he became involved in an unsuccessful railroad

venture and two years later moved to Mandarin. He lived yet another fourteen

years. Sammis was buried in the small cemetery at Clifton, close to his

Arlington home. His property there was sold in 1873 to a church colony

from New Jersey, which used it as a resort for its members. Named the Ocean

Grove Association, it subdivided the property into residential lots. The

Sammis house, called the Florida Winter Home, served as a hotel for tourists

and prospective buyers of land in the vicinity. At the time a large two-story

wing was added to the building. A brochure issued in 1873 reveals the configuration

of the house before the addition of a columned portico. The church group

soon folded. The property was sold to William Matthews, a Philadelphia

businessman.

Post-Reconstruction to the Turn-of-the-Century (1878-1900)

The pace of development in northeast Florida

quickened during prosperous years that followed the war and its traumatic

aftermath, known as the Reconstruction Era. The building boom was fueled

by an influx of new settlers and tourists, drawn to Florida in growing

numbers. Its rail and steamship connections made Jacksonville a popular

tourist destination. A steamboat trip up the St. Johns and Ocklawaha rivers,

reaching almost the center of the Florida peninsula, became a favorite

excursion for Americans wealthy enough to afford it. The trip began at

Jacksonville, where by 1880 some forty hotels and numerous boarding houses

had been constructed to accommodate the estimated annual 75,000 visitors.

The most significant building was the St. James Hotel. which dominated

Jacksonville's skyline until its destruction by fire in 1901.

Real estate companies catered to the visitors,

encouraging them to make northeast Florida their second or "winter" home.

A growing number of new residents took up lands on the east bank of the

St. Johns River, where bluffs rise sharply above the water, offering a

high, wooded, and picturesque location. Robert Bruce Van Valkenburg, a

former congressman from New York, Union officer, and minister to Japan

from 1866 to 1869, purchased an eighteen-acre site on what is now Empire

Point in 1870. He ostensibly retired to Florida to recover his health,

but almost at once plunged into local political life, winning an appointment

as Associate Justice of the Florida Supreme Court. Denounced by the Tallahassee

Weekly

Floridian as a "carpet-bag" jurist, he nevertheless served on the bench

from 1874 until his death in 1884. Van Valkenburg's house on Hazzard's

Bluff. now Empire Point, remains standing at 1231 Glengarry Road.

In the same vicinity, another former Union

officer, Gelleral Alexander S. Diven, a New York lawyer and legislator,

purchased the site on Hazzard's Bluff where in the 1850s John Clark had

operated his saw mill. One of many travel accounts of Florida, published

in 1885, described the residence that Diven built there as follows:

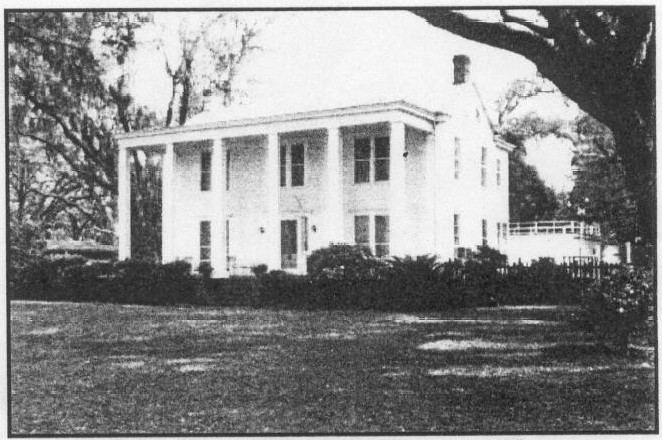

The Diven-Dunkee House, 4749 River Point Road, circa 1877.

The first place situated on the peninsula formed by the confluence of the St. Johns River and Arlington Creek is the property of General A. S. Diven, one of the most beautiful places in St. Nicholas. It contains 34 acres, and the mansion, a fine large house surrounded by a broad piazza, is distant from the landing some 200 yards.

A neighbor of Diven's was Major Joseph H. Durkee, another former Union officer. His son, Dr. Jay H. Durkee, purchased the Diven residence from General Diven's son, George, in 1909. It was the Durkee heirs who in the 1950s subdivided the surrounding ninety acres into the Empire Point subdivision. Until that time, the Diven House and Marabanong (see next page) were among the very few residences perched upon the bluff, which from a vantage point on the south bank of the Arlington River overlooks the confluence of the Arlington and St. Johns rivers.

continued on jackvil7.htm ...............