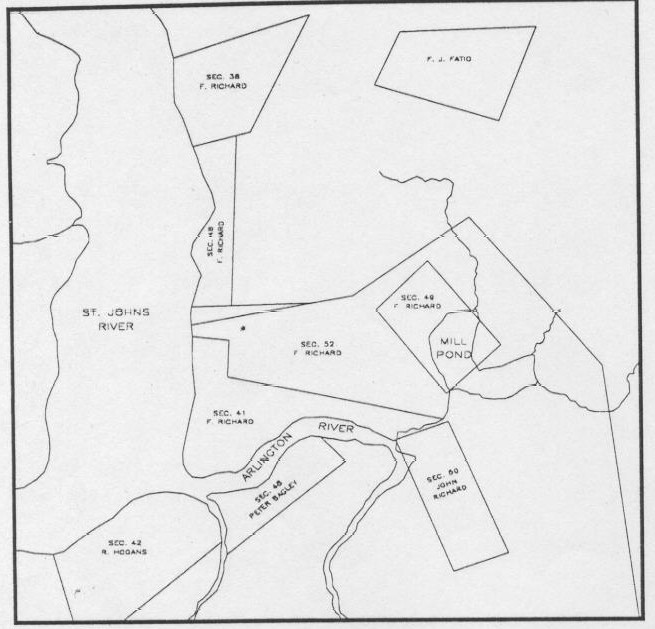

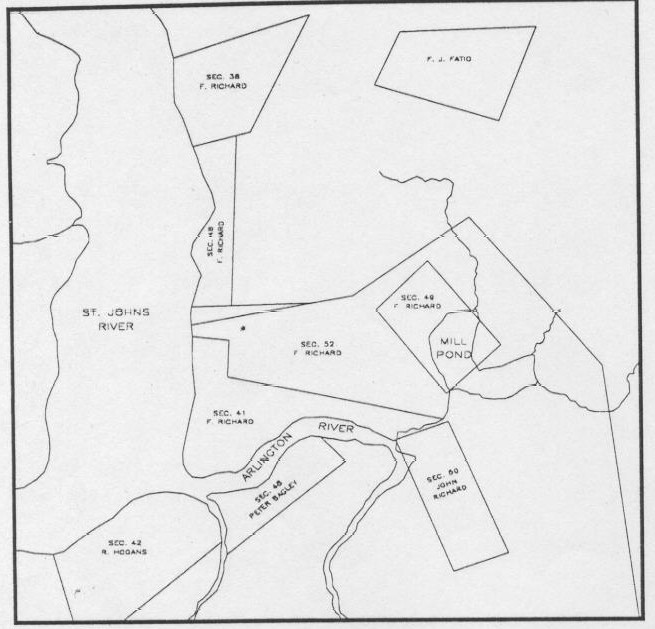

Spanish Landgrants in the Arlington area (as of 1821)

Spanish Landgrants in the Arlington area (as of 1821)

During the First Spanish Colonial Period (1565-1763),

the Spanish regarded the St. Johns River primarily as a defensive barrier

against Indian and English encroachment upon the colonial capital at St.

Augustine. They built a series of forts or outposts along the east bank,

extending from the river's mouth some sixty miles southward to Picolata.

The Spanish did not, however, exploit the resources along the St. Johns.

They occupied Florida to prevent their European enemies from establishing

a military position on the peninsula and to provide a base for missionary

expeditions among the Indian tribes of the southeastern part of the continent.

Spain failed to settle permanently any area of Florida except the immediate

environs of St. Augustine.

Beginning in the mid-seventeenth century,

the Spanish governors issued large tracts of land to prominent local families

as a means of encouraging the development of an agricultural and livestock

economy. Eleven grants were carved out along the banks of the St. Johns

River, reaching from its mouth to the southern tip of present-day Lake

George. The location of the present city of Jacksonville at one of the

narrowest points on the lower St. Johns made it an important fording point.

Indians called the place Wacca Pilatka, translated as a place where cows

cross .

For its part in backing the defeated French

in the Seven Year's War, the Spanish Crown was forced to surrender Florida

to England in 1763. The Spanish inhabitants, with few exceptions, evacuated

the colony. To encourage demographic and economic growth the British instituted

a liberal land policy. By 1776, they had awarded 114 grants to 1.4 million

acres of Florida land. Success in attracting settlers to the British colony,

however, depended on resolving jurisdictional conflicts with the Indians.

In November 1765, Spanish officials and Indian leaders agreed to limit

English settlement to the northeastern region of the colony. including

the largely unexploited St. Johns River valley. That same year the Marquis

of Hastings was granted 2,000 acres of land encompassing much of present-day

Jacksonville. Like most grants at the time, however, it came to no result.

Only sixteen grants were settled at the beginning of the American Revolution.

The outbreak of rebellion in the thirteen

colonies to the north dramatically altered the development of British Florida.

Since the Florida colonies remained loyal to the crown, they attracted

large numbers of refugees seeking economic stability and political asylum.

The population of East Florida (that part of the peninsula east of the

Suwanee River) swelled from approximately 3,000 in 1776 to 17,000 eight

years later, with most of the immigrants coming from rebel- controlled

Georgia and South Carolina. Many of the new immigrants settled in and around

St. Augustine and along the St. Johns River.

From 1784 until 1821 Florida once again came

under Spanish rule. The transfer from British control initially slowed

development, since the majority of settlers left the colony for the United

States, the Bahamas, or other parts of the British Empire. The population

of East Florida fell to under 2,000 and numerous plantations were abandoned.

Emulating the British, the Spanish Crown adopted a liberal land policy.

An oath of loyalty to the Spanish government was the only requirement for

land ownership. Contrary to official royal policy elsewhere in the Spanish

empire, the crown permitted non-Catholics to settle in Florida. Several

grants included lands on the east side of the St. Johns River. The largest

of them was given in 1817 to Francis Joseph Louis Richard, whose lands

embraced some 16,000 acres. Richard received much of the territory north

of the Arlington River. Samuel Russell later filed a petition claiming

650 acres at the mouth of Pottsburg Creek, given to him in 1795. Russell

farmed the acreage with his wife, two sons, and seven slaves. Reuben Hogans,

a sergeant in the provincial militia, received 200 acres, comprising much

of what is now Empire Point. Peter Bagley received a small tract lying

south of Pottsburg Creek (now the Arlington River) and northeast of Little

Pottsburg Creek.

Francis Richard left an enduring legacy

in Arlington. A native of Italy, he immigrated to the United States from

Santo Domingo, where he had owned a sugar plantation, arriving in East

Florida in 1797. He and his wife, Genevieve Bianne, a native of Santo Domingo,

produced four children, William R. Richard, Clementine Honorine Richard,

Francis Richard, and John Charles Richard. Francis Richard II, in turn,

named one of his sons Francis, resulting in some confusion in the historical

record. It was apparently Francis II who in 1817 petitioned the Spanish

Governor for land upon Strawberry Hill upon which to erect a saw mill.

Richard's holdings eventually embraced some 16,000 acres and extended nine

miles southward from the mouth of the Arlington River and four miles eastward

from the water. Francis I died in Georgia several years later and his widow

followed him in death in 1821. Francis II died in 1839, leaving the mill

and the bulk of the estate to Francis III. The grant of land that Richard

and the Richard heirs obtained and the additional property they acquired

formed the basis for much of Arlington's later development.

In the early years of the nineteenth century

the United States grew increasingly anxious to acquire both East and West

Florida. The vast, largely undeveloped area proved tempting to the expansionist

government and, as well, to private land speculators. Moreover, the Floridas

presented problems for the United States. They offered haven to runaway

slaves and Seminole Indians, who often engaged in armed conflict with settlers

residing along the southern limits of the United States. East Florida,

in particular, provided a setting for contraband trade and slave smuggling,

both of which conflicted with the policies and laws of the United States

government. Finally, the Floridas, sharing a border with the United States,

constituted a potential threat to national security. The relative ease

with which Andrew Jackson invaded Florida during the First Seminole War

made it apparent that Spain could no longer ensure the security of its

Florida colony. Mounting pressures from the United States forced Spain

to sign the Adams-Onis Treaty in 1819 and cede Florida to the United States,

although diplomatic delays postponed actual transfer of the provinces until

1821.

The United States Territory of Florida was

established in 1821 and Andrew Jackson named Provisional Governor. St.

Johns and Escambia counties became the first political subdivisions in

the newly-formed territory. St. Johns County initially encompassed all

of Florida east of the Suwannee River. In 1822, Duval County, the fourth

county established, was carved out of St. Johns County. Named for William

Pope DuVal, the first territorial governor of Florida, the jurisdiction

included a number of present-day counties in Northeast Florida. At Cowford

a group of property owners, led by Isaiah D. Hart, subdivided their land

into streets and blocks and renamed the settlement Jacksonville in honor

of the popular Seminole War hero.

After the United States acquired Florida, settlers

began to stream into the new territory. Land speculators and entrepreneurs

saw potential fortune in its underpopulated interior regions. Real estate

speculation ran rampant during the early years of the territorial period,

but transportation and health problems limited actual settlement. The first

Territorial Census in 1825 found 5,077 residents in East Florida, which

remained largely wilderness.

As part of the Adams-Onis Treaty the United

States government agreed to confirm Spanish land grants to recipients who

had fulfilled the terms of their contracts. The federal government set

up a Board of Land Commissioners for East Florida, which reviewed the cases

of all individuals claiming possession of Spanish grants. In 1830 the United

States Congress, acting upon the recommendations of the board, confirmed

title to legitimate grantees. The actions of the board and Congress maintained

continuity of !and holding patterns between the Second Spanish and American

Territorial periods and provided a solid base for subsequent settlement

that was absent from previous changes of possession.

Emigration of Americans from the southeastern

seaboard into Florida intensified during the 1820s and 1830s when the lumber,

cotton, and sugar industries dominated the state's economy. With a vast

expanse of relatively cheap and fertile land, Florida became an attractive

destination for families from agricultural states throughout the South.

During that period Jacksonville became the primary shipping point for agricultural

produce from the interior regions of northeastern Florida. The processing

and shipping of lumber ultimately became the fledgling community's most

prominent industry. Commercial citrus production also played a vital role

in the local economy until 1835, when a severe freeze devastated orange

groves throughout the region.