(sturgis8.jpg)

More on: http://www.harvard-magazine.com/issues/so97/vita.html

See note for achievements of these 3 generations of Bigelows with MA

general Hosptial.

See "Forge" Apr 1999, Vol. 28, No. 2,p. 28.

Article written by Thomas LaMarre for "Money Talk", a copyrighted

production

of the American Numismatic Association, 818 N.Cascade Av., Colorado

Spgs,CO

80903,e-mail ana@money.org, contributed by Phillip Bigelow, Bellingham,

WA.

Related "Forge" articles:

Vol. 20, No.3, Jul. 1991,

Vol.21, No.2, Apr 1992,

Vol.22,No.1,Feb 1993.

The secretary of the Harvard class of 1871

once wrote to William Sturgis Bigelow requesting some news, "or a

story." Bigelow replied, "Story? God bless you, I have none to tell,

sir. Since '81 I have spent about seven years in Japan, when [sic] I

saw a great many folks of

high and low degree, got together some things of various sorts for the

Boston

Museum of Fine Arts...and learned a little about Eastern philosophy and

religion. I have neither wife nor children, written no books, received

no special

honors and I belong only to the regular clubs and societies."

This extraordinary understatement combined

Buddhist self-abnegation with the inner confidence of an affluent,

private, and talented Boston Brahmin. In fact, those "things of various

sorts"--numbering, according to one estimate, 26,000 pieces of

painting, sculpture, ceramics, and manuscripts--formed the heart of one

of the world's greatest museum collections.

As to the Eastern philosophy, he studied and

then embraced Buddhism, as did his friend Ernest Fenollosa, A.B. 1874.

Bigelow's 1908 Ingersoll Lecture at Harvard explained "Buddhism and

Immortality" in scholarly detail, and was later published.

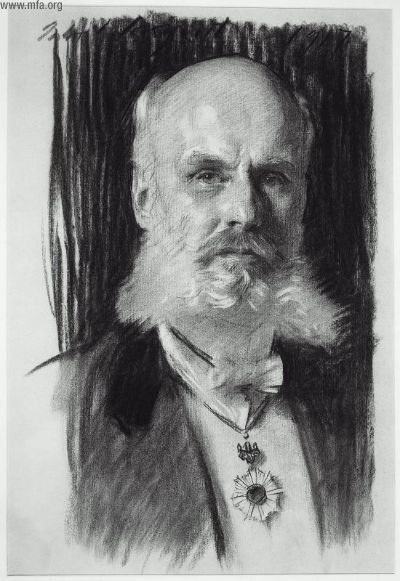

Bigelow was truthful in saying he had no wife

or children, but not in denying that he had written books or received

honors. Japan awarded him the Imperial Order of the Rising Sun, with

the rank of Commander, the highest distinction bestowed in that country

on persons not in official life (he wears it in the charcoal portrait

above, drawn by his friend John Singer Sargent).

Bigelow was profoundly affected by the death of

his mother when he was three. (His Ingersoll

Lecture states that "Maternal love is the source

of all human virtues.") His father, the renowned surgeon Henry Jacob

Bigelow, was

something of a martinet, and young William was evidently something of a

rebel:

his

report card from the Private Latin School in 1865 rated him

twenty-second academically

in a class of 55, but fifty-fourth in "conduct."

After graduating from Harvard Medical School in 1874, Bigelow went

to Europe.

He

stayed five years, studying in Vienna, Strasbourg, and finally in Paris

under Pasteur. He

brought back to Boston the new research on bacteria, and established

privately one of

this country's first laboratories in that field. This displeased his

father,who

wanted the line of distinguished Bigelow surgeons at Harvard and

Massachusetts General

Hospital to continue. William was duly appointed surgeon to outpatients

at the MGH. "Few men,"

wrote medical historian John F. Fulton, "could have less taste for

surgery than the

sensitive Bigelow, and it was not long before he gave up all thoughts

of practice."

In 1881, believing that the world was moving too fast and that much

of life in Boston

was ugly, he went to Japan, following Edward S. Morse and Ernest

Fenollosa, who were

among the first Americans to study Japanese culture. He later called

the cruise to Japan

the turning point of his life. During his prolonged stay he studied,

traveled, and collected the

treasures that the Japanese were discarding in their rush to become

Westernized.

After returning to Boston in 1889, Bigelow devoted much of his time to

the study of art

and Asian religions. He also entertained lavishly at his home at 56

Beacon Street, often

welcoming such College friends as George and Henry Cabot Lodge, Brooks

and Henry

Adams, and Theodore Roosevelt, who regularly made Bigelow's home his

Boston

headquarters. He became an active trustee of the Museum of Fine Arts

and continued to

collect paintings, often consulting with Isabella Stewart Gardner.

Reportedly somewhat

reserved in his dealings with the opposite sex, he once wrote to her

coyly, in the third

person: "She is very attractive." At his favorite spot in America,

however, a summer

house on tiny Tuckernuck Island, off the shores of Nantucket, he

entertained men only,

and his guests wore pajamas, or nothing at all, until dinnertime, when

formal dress was

required. A staff of servants provided food and fine wines; the library

contained

3,000

volumes,"spiced with racy French and German magazines," one chronicler

reported.

Henry Adams described Bigelow's retreat as "a scene of medieval

splendor"; George

Santayana, A.B. 1886, may have modeled Dr. Peter Alden, the father of

the protagonist

in The Last Puritan, after Bigelow.

The Boston Evening Transcript, the unofficial gazette of Boston's

Brahmins, ran two

bold headlines on October 6, 1926. One told of Babe Ruth's still

unexcelled feat of hitting

three home runs in a World Series game, but the larger headline

reported the death of

William Sturgis Bigelow. His funeral, at Trinity Church, was conducted

by his classmate

William Lawrence, the former Episcopal bishop of Massachusetts. His

ashes were

divided. Half were interred in Mount Auburn Cemetery, which had been

envisioned by

his grandfather Jacob Bigelow as a spiritually uplifting as well as

"hygienic" burial site.

But the rest were buried by a Buddhist temple, overlooking Bigelow's

favorite lake in

Japan.

Sources:

Bigelow Society,The Bigelow Family Genealogy, Vol II, pg 114;

Howe, Bigelow Family of America;

FORGE, The Bigelow Society Quarterly. Vol.6, No.2, pg 23-24

Encyclopedia of American Biography;

records of Mt. Auburn cemetery, Cambridge.

FORGE, The Bigelow Society Quarterly. Vol.6, No.2, pages 23 and

24, has an interesting article on William S. 8, Henry Jacob 7 and the

grandfather Jacob 6

- all learned

physicians/Surgeons and the dedication of the upper eight stories of

the

thirteen story Massachussette General Hospital building to these three

generations

of doctors.

From Guy Bigelow:

Referring to the book that was published by "Bob Vila's This Old House

- 1981" following the TV program which covered the remodeling of Dr.

Henry J. Bigelow's home in Newton, I find no specific address given for

the property. It was, however, located on the top of Oak Hill which is

a high point in the Newton area. Current maps of the area around Newton

show a residential subdivision approximately 3 miles south and a bit

east of Newton, city center. This may be the area where the old Bigelow

house is located. More specific information might be obtained by

contacting the Newton Historical Preservation Association or the Newton

Chamber of Commerce. I have no information on contacting either of

these organizations but you might search on the internet. Guy Bigelow

Note:

Tuesday 06/10/2003 7:29:55pm

Name: Isabel Bigelow

E-Mail: isabelbigelow@hotmail.com

Comments:

I am interested in William Sturgis Bigelow. Don't know if I am

related but searching him got me to this page

.

.

(/rod2005b/sturgis1.jpg)

(/rod2005b/sturgis2.jpg)

From: http://www.yesterdaysisland.com/05_articles/satire/tucker.html

Part I

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

by James Everett Grieder

There’s a stretch of coastline on Tuckernuck Island that has the unique

distinction of being named for a person. Most places on the

island

are distinguished somewhat more pragmatically: North Pond, East Pond,

South

and North Shores; Bigelow’s Bluff alone is a namesake. Never mind

the

fact that the particular spot so named is by now far out to sea —

wherever

that part of the shore terminates it will always be named after one of

the

most remarkable men to ever grace the island: William Sturgis Bigelow.

Born on April 4, 1850, William Sturgis Bigelow was the son Henry Jacob

Bigelow and grandson of Jacob Bigelow, neither of whom were slouches in

the “remarkable men” department themselves: Jacob Bigelow was a

physician at Massachusetts General Hospital for twenty years (there’s a

wing named after him), established Mount Auburn Cemetery (which served

as a model of sanitation for many later burial grounds) and, while at

Harvard University teaching science, coined the term “technology”; his

son, Henry, studied medicine under his father at

Harvard, eventually becoming a professor there as well as chief of

surgery at Massachusetts General. Perhaps his most far-reaching

achievement was to sponsor the first public demonstration of the

efficacy of anaesthesia in surgery (the artist Robert Hinkley captured

the moment in his painting, “The First Operation with Ether” – Bigelow

is the third man from the right, with his hand on his chest).

Plainly, Bigelow had some big surgical gloves to fill. Scion of

the Scollay and Sturgis families as well as the Bigelows, Boston

Brahmins all, great things were expected of young William, and he did

indeed achieve greatness of a sort, although perhaps not the kind that

his dour martinet of a father might have intended. William’s

mother died when he was three years old,

an event that would have a profound effect on the sensitive young

man. An indifferent student, Bigelow’s report card in 1865 notes

that he fell in

the middle of his class academically but was next to last in “conduct.”

Nevertheless,

Bigelow managed to graduate from Harvard Medical School in 1874 and

immediately

embarked for Europe for additional study, as his father had done during

his

days as a newly-minted student. While in Paris, Bigelow studied

under

Louis Pasteur, eventually returning to the United States with the

latest

research in the newly-created field of bacteriology; Bigelow would go

on

to privately fund one of the first laboratories in that field.

Upon his return to Boston in the early 1880s, Bigelow appeared to be on

track for a distinguished career in medicine, following in the

footsteps

of his venerated father and grandfather. In the winter of

1881-82,

however, Bigelow’s life took a quite unexpected turn; he attended a

series

of lectures by Edward Morse, a professor of Comparative Anatomy and

Zoology

at Bowdoin College. A few years previously Morse had been invited

to

the Imperial University of Tokyo in order to organize a department of

zoology;

during a return trip to the United States, he gave a series of lectures

on

Japan at the Lowell Institute in Boston. These lectures

captivated

the interest of many of Boston’s intelligentsia, including William

Sturgis

Bigelow, no doubt to the great alarm of William’s father Henry.

Later that year, after declaring his belief that the world was moving

too fast and that much of life in Boston was “ugly,” Bigelow announced

his plan to travel to Japan with Edward Morse and Ernest Fenollosa, a

young Harvard Divinity student that Morse had recruited during an early

trip to Boston. William, sensitive as he was, was never cut out to be a

surgeon, and he probably would have left his pre-determined career path

anyway. Entranced by the Japanese aesthetic and supportive of

Fenollosa's efforts to conserve Japanese

ancient temples and monuments, Bigelow determined that he had to see

them

for himself. One cringes to imagine the scene at the breakfast

table

when young William conveyed the news to his father — glacial doesn’t

begin

to describe it. William’s financial future was secure, however —

he

had inherited a massive fortune from his mother, who had been heir to

the

extremely wealthy Sturgis family of Barnstable on Cape Cod.

Bigelow and Fenollosa became quite close. Both men were ardent

Japanophiles and amassed enormous collections: Fenollosa specialized in

Chinese and Japanese paintings, while Bigelow purchased literally tens

of thousands of pieces of

lacquer ware, swords, statues, and wood block prints. However,

theirs was more than simply the self-aggrandizing purchases of the

mega-rich; they truly saw themselves as saving important pieces of

Japan’s past, at a time when few others took notice, including many

Japanese themselves: at the time the island nation was rushing to

modernize itself in the face of Western imperial

power, and the old ways were deemed unimportant and not worth

saving. In 1885, both Fenollosa and Bigelow converted to

Buddhism, studying with a

Tendai Buddhist master and dressing in Japanese robes (again, one can’t

help

but wonder what that first trip home to the Bigelow family’s townhouse

on

Beacon Hill must have been like).

Over the next few years Fenollosa and Bigelow played host to a number

of Bostonians who, fired in part by Morse’s lectures, visited Japan,

eager to gain some insights into Buddhism. Among their

distinguished guests were

Isabella Stewart Gardner (an important art collector in her own right,

whose

home later became the Gardner Museum) and the author Henry Adams, who

had

traveled to Japan with his friend, the painter John La Farge.

Adams was seeking escape in the Far East from the intense grief he felt

over the recent suicide of his wife Clover. A short (further)

digression away from the shore of Tuckernuck is necessary to detail the

short unhappy life of Clover, which is intimately connected to that of

Bigelow.

Clover’s real name was Marian Sturgis Hooper; she was William’s first

cousin. Clover’s mother, Ellen Sturgis Hooper, was a poet and a

member of the Transcendental Club (her sister, Susan Sturgis Bigelow,

William’s mother, was also a member). Ralph Waldo Emerson

regularly solicited poetry from her for his periodical The Dial, and

Thoreau included the end of Hooper’s “The Wood-Fire” in the chapter

“House-Warming” in Walden. Ellen Sturgis Hooper often hosted

gatherings of like-minded individuals at her home, where it would not

have been unusual to see such luminaries as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Oliver

Wendell Holmes, and Henry James. Quite an inspiring home for a

sensitive young girl, or so it would seem; sadly, Clover’s family had a

tragic thread of mental

illness and suicide that ran through the generations. Clover was

present

when her aunt (William’s mother), Susan Sturgis Bigelow, died,

allegedly

from arsenic poisoning at her own hand, although tuberculosis was the

polite

reason given. In 1887, Clover’s sister Ellen walked into an

oncoming

train, and in 1901 her brother Edward leaped from the third floor of

his

home, surviving briefly before eventually succumbing to pneumonia.

Clover was five when her mother died of tuberculosis; she was extremely

close to her father, Dr. Robert Hooper. Both Clover and her

sister

Ellen often accompanied their father on visits to Worcester Asylum for

the

mentally ill, where they witnessed the dreadful effects of mental

illness

and the almost medieval state of psychiatric treatment at the

time.

Clover was deeply affected by the horrors of such confinement, and her

surviving letters make it quite clear that she regarded suicide as

preferable. On learning of the suicide of William Morris Hunt,

who had painted a portrait of Henry Adams’ father, she wrote “He has

put an end to his wild, restless, unhappy life. Perhaps it has

saved him years of insanity which his temperament

pointed to.” These experiences left Clover a shy, retiring

nervous

girl, fearful of being separated from her father for any length of time.

See Part 2 below to find out what happens to Clover …

Tuckernuck’s Resident Millionaire Buddhist

The Story of Bigelow’s Bluff

Part 2

There’s a stretch of coastline on Tuckernuck Island that has the unique

distinction of being named for a person. Most places on the

island

are distinguished somewhat more pragmatically: North Pond, East Pond,

South

and North Shores; Bigelow’s Bluff alone is a namesake. Never mind

the

fact that the particular spot so named is by now far out to sea —

wherever

that part of the shore terminates it will always be named after one of

the

most remarkable men to ever grace the island: William Sturgis Bigelow.

Part II of this article, picks up just as William’s first cousin,

Clover, is about to marry…

Clover’s prospects brightened, however, when she met the young

Henry Adams. Adams, the grandson of John Quincy Adams and

great-grandson of

John Adams, was the heir of yet another prominent Boston Brahmin

family, and

was beginning to establish a reputation for himself as an author and

historian

in his own right. A marriage between these two was a favorable

one

socially, but, while there was apparently great fondness between them,

Clover’s

nervous disposition eventually drove Henry into a (unconsummated)

relationship

with another woman, Lizzie Cameron, the niece of William Tecumseh

Sherman.

Their letters demonstrate their great, if frustrated, passion for one

another;

if Clover had any knowledge of the long-distance love affair she made

no

mention of it. Perhaps she was too immersed in worrying for her

own

health and safety.

While honeymooning in 1872 along the Nile, Clover suffered a nervous

breakdown; this was the first time that she had been apart from her

father for any length of time. Upon her return to Boston she

discovered a passion for photography, but the limitations of her gender

at that time, combined with a lack of support from her husband,

resulted in her talents being limited to family portraits. The

death of her father in the spring of 1885 sent Clover spiraling into a

mental depression from which she did not recover. On December 6, 1885,

Henry

Adams found his wife lying on the floor, a vial of potassium cyanide —

used

to process photographs — by her side. A doctor was summoned, but

it

was too late. Clover was dead.

Adams’ trip to Japan was an attempt to dull the painful loss. His

friend John La Farge was the one who suggested the idea. La Farge

had

been a pioneer in collecting Japanese art and incorporating Japanese

effects

into his work, beginning in the 1860s (he also married Margaret Perry,

the

niece of the Commodore who had opened Japan to the West over the barrel

of

a gun). In 1869, La Farge wrote an essay on Japanese art detailing the

asymmetry and heightened color of Japanese prints, which looked empty

and unbalanced by traditional Western standards. The radical

qualities of La Farge's art in the 1860s were more subtly incorporated

into his work over the subsequent decades. Stunning examples of

La Farge’s work in stained glass (the brilliant coloring of which may

have been influenced by his interest in Japan), may still be seen at

Trinity Church in Boston, and he became increasingly involved in large

scale decorative and mural projects, both for churches and

the residences of America's newly-minted millionaires.

In 1886, La Farge was again embarking for Japan and asked his grieving

friend Henry Adams to join him; perhaps a further incentive was the

thought of seeing his late wife’s cousin. Although not as smitten

with the lure of the Orient was his companions, Adams was apparently

deeply moved by images of Kannon, the feminine Japanese embodiment of

the wisdom of compassion. When he returned to the United States,

Adams commissioned the famed sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens to create

a Kannon-inspired statue for his wife's grave

in Rock Creek Cemetery, Washington, D.C. (La Farge's painting of Kannon

by

a waterfall may have served as inspiration for the artist). That

statue

is widely considered to be Saint-Gauden’s masterpiece, and may be

viewed

to this day in Rock Creek Cemetery. If you visit, take a moment

to

remember poor Clover, please.

Bigelow returned to Boston in 1889, and devoted much of his time to the

study of art and Asian religions; following in the footsteps of Morse

he

lectured widely on Buddhism, and played a key role in developing

diplomatic

and cultural relations between the U.S. and Japan. Bigelow

donated

his collection and expertise to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts as a

trustee;

he brokered the purchase of Fenollosa’s collection through another

Harvard

doctor, Charles Goddard Weld (yes, as in former Governor Weld) and by

the1890s,

the MFA had one of, if not the pre-eminent collection of Far Eastern

art

outside of Asia. Its first curator was Fenollosa, who had

returned

from Japan with Adams and La Farge, and who was instrumental in

establishing

the collection.

A year after William Sturgis Bigelow returned from Japan, his father

died following a carriage accident. In 1906 Bigelow purchased 56

Beacon Street

in Boston, where Henry Adams, college chums George and Henry Cabot

Lodge

(cousins of the Adamses), and even Theodore Roosevelt could be found

visiting.

Roosevelt made Bigelow's home his Boston headquarters, and presumably

it

was there that Bigelow had an effect on U.S. foreign policy. No

doubt

aware that the manly Roosevelt would be less than impressed with highly

lacquered

teapots Bigelow instructed the Rough Rider in the finer points of

Japanese

culture by throwing him repeatedly using judo holds. Roosevelt

was

so impressed that he had a special Judo Room set aside in the White

House

— he also signed a treaty with Japan.

But what does all this have to do with a bit of shoreline on

Tuckernuck? I was just getting to that — you needn’t be in such a

hurry! Bigelow would often escape from the heat and noise of

Boston to his large, rambling summer “cottage” on the west end of

Tuckernuck. Perhaps one of the few

pieces of common ground shared by William and his father Henry Jacob

Bigelow,

literally, was their love for the island. Henry was an avid

gunner

and after visiting the island briefly had returned and rented a

cottage, and

then leased land, from Charles Dunham; in 1871 he had built a simple,

boxy

house on the land, even though the property wasn’t really his.

Bigelow

suffered the misfortune of hiring my grandmother’s great-grandfather,

James

Cochran Dunham, as his caretaker (my wife’s family owns “Grandfather’s

House”

on Tuckernuck — James Cochran is the eponymous grandfather, and former

owner).

Dunham contemptuously viewed the senior Bigelow as having more money

than

brains, and set out to take this “summer person” for all he could

(thankfully,

this attitude does not prevail today on Nantucket).

In 1871 Bigelow tired of the constant gouging and fired Dunham as his

caretaker. Dunham, a true Tuckernucker, was not one to let an

opportunity for a good feud to pass by, and began harassing Bigelow,

denying access across his own property to the rest of the island and

sending his sons out to chase the birds

away that Bigelow was hunting. Bigelow sued Dunham and won;

Dunham appealed

and lost, and the fine was doubled. Unable to pay, Dunham was

forced

convey half of his farm to Bigelow. Bigelow also eventually

purchased

the land he was leasing and set about enlarging the building on it in

order

to accommodate his son William, their guests and their servants; he

hired

my cousins the Smiths and the Sandsburys to do the job. As with

cousin

Clover, both Henry and William had an avid interest in photography, and

they

took many pictures of the construction of their new house, and

Tuckernuck at that time, including many members of my extended family.

In addition to his beloved photography, Bigelow kept careful track of

the almost constant erosion of Tuckernuck's north and west shores:

"...very heavy surf...6 to 10 feet cut off the bank," he wrote in

1904. "The last of

the road around Robert [King Dunham]'s lot went, leaving about a foot

to

squeeze by on.....The smallest loss in any one year since was 10 paces;

the

largest 39." In 1908: "About 70 feet of bank cut off.

Charley Brooks gives it eight years to the corner of the tennis

court. I guess six".

Bigelow entertained many of his distinguished friends at his island

retreat, including Roosevelt, Henry Adams, John La Farge, Senator Henry

Cabot Lodge, and Bishop William Lawrence, who had been John La Farge’s

sponsor at Trinity Church in Boston. To get there they took a

train from Boston to Woods Hole, followed by a three-hour trip on a

side-wheel steamer to Nantucket, a bone-jarring wagon ride to Madaket,

then a private boat jaunt to Tuckernuck itself. It was strictly a

men-only affair, and his guests wore typically wore Japanese dress, or

nothing at all, until dinnertime, when formal dress was required.

A staff of servants, including cook and butler, provided food and fine

wines; Bigelow had one room converted into a darkroom to develop

photographs, and amassed a library contained 3,000 volumes to keep his

visitors entertained when the weather turned foul. The

collection, complete with

racy French and German magazines (which probably would seem quite tame

to

us today) topped off an experience that Henry Adams described as “a

scene of medieval splendor”.

In his poem “Tuckanuck,” dedicated to "W.S.B." (William Sturgis

Bigelow), he describes the philosophy of the group:

I am content to live the patient day.

The wind, sea-laden, loiters to the land,

And on the naked heap of shining sand

Th’eternity of blue sea pales to spray.

In such a world no need for us to pray:

The holy voices of the sea and air

Are sacramental, like a peaceful prayer

Wherein the world doth dream her tears away.

We row across the waters’ fluent gold,

And age seems bless~d, for the world is old.

Softly we take from nature’s open palm

The dower of the sunset and the sky

And dream an Eastern dream, starred by the cry

Of sea-birds homing through the mighty calm.

These halcyon days were soon to end, however; in the late summer

of 1909, George Cabot Lodge fell ill while visiting Tuckernuck, and

before medical aid could reach him, he died. He was only 35 years

old. Henry Cabot Lodge never returned to Tuckernuck and his

friend’s death affected Bigelow

deeply. For several years he stayed away from his beloved island,

finally

returning after a three year absence — but the original spirit of joie

de

vivre had vanished. "It is inexpressibly sad here, since 'Bay'

(Lodge)

left,” he wrote later that year..

In 1926, at the age of 76, William Sturgis Bigelow died. His body

was laid in state in his Buddhist robes in his home at 56 Beacon Street

in

Back Bay; his funeral at Trinity Church was conducted by his classmate

and

friend William Lawrence, the former Episcopal bishop of

Massachusetts.

Bigelow’s ashes were divided: half were interred in Mount Auburn

Cemetery,

the cemetery founded by his grandfather, while the other half were

buried

near Homyoin Temple in Japan, the site of his Buddhist initiation,

overlooking

Bigelow's favorite lake. In his will Bigelow left a fund to

Harvard

University for the advancement of Buddhist studies, but his

accomplishments

can never be measured by money alone. According to one estimate,

Bigelow

left 26,000 pieces of painting, sculpture, ceramics, and manuscripts to

the

Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and is responsible as much as anyone for

bringing the Eastern aesthetic to America. Through his tireless

work he influenced creative souls as diverse as Ezra Pound and Frank

Lloyd Wright, and through them countless others. Boston may have

lost a fine doctor, but the world

gained so much more in return.

There is a further, personal postscript to this story. Bigelow

did make an exception to his “no women” policy – in 1898 he offered his

Tuckernuck estate to his niece Mabel Hooper (Clover’s surviving sister)

who had married John Louis Bancel La Farge, for their honeymoon.

They fell in love with

the island, and their descendants remain there still. John Louis

also

met and befriended my great-great-grandfather, Erastus Chapel, of whom

he

said “everything about him is round, his legs, his belly, his arms and

his

shoulders, his head...and to top all, his little white hat”— the apple

doesn’t

fall far from the tree, apparently, that being a fair description of

this

author. Erastus had purchased a lot from William Sturgis Bigelow

in

1893 (part of the old Dunham property won in the lawsuit — what’s more,

Erastus

married James Cochrane Dunham’s niece), and built a house there.

John

Louis also mentions that Erastus was quite close to his son, whom he

referred

to as “the boy,” even when the “boy” was forty years old; that boy was

James

Everett Chapel, whom I am named for, and who is the former owner of the

house

at 31 Union Street where I now reside with my family (the house now

belongs

to my great-aunt, Mary Chapel Humphrey, and her children).

As William had feared, erosion eventually claimed the Bigelow estate on

the west end of Tuckernuck, including the house in 1944. Before

that

occurred, Mabel arranged to have Bigelow’s old library transported from

the

west end to the east, where she had bought some property was building a

new

house, designed by her son Louis, who was an architect. In 1939

Mabel

hired my great-grandfather, along with several other men, to move the

building for her. They placed it on long timbers resting on wagon

wheels, and over the course of a month moved it to the east end of the

island. That

library building was incorporated into the new house, and remains there

to

this day.

The La Farge family also sold a piece of the same Dunham property to

James Everett Chapel, and it is on a portion of that property that my

family’s house,

the Pond House, still stands. When I look out of the kitchen

window

of our little house, I can see Bigelow’s Bluff; nothing physical

remains to

note the passage of this remarkable man, but his contribution to art

and to

history, and the strong bonds of friendship between his family and mine

that

remain to this day, provide a greater monument than any house or statue

ever

could.

I am deeply indebted to the patient research found in Wayman Coffin’s

book Tuckernuck Island, as well as the stories told to me over the

years by my grandmother, Ruth Chapel Grieder, for much of the

Tuckernuck information found

here. For more information on Bigelow, La Farge and Boston’s

Japanese

connection please check out The Great Wave : Gilded Age Misfits,

Japanese

Eccentrics, and the Opening of Old Japan, by Christopher Benfey.

Tuckernuck:

Bigelow & His Tuckernuck Retreat

by Frances Kartunen

Tuckernuck School c. 1930s with 3 young girls and a teacher

courtesy Nantucket Historical Assn

Off Smith’s Point, the extreme western tip of

Nantucket,

lie two small islands, Tuckernuck and Muskeget. Tuckernuck, the

nearer

of the two, is plainly visible from anywhere along Nantucket’s North

Shore,

from Jetties Beach to Madaket. Its Algonquin name is said to mean “loaf

of

bread.” Tiny, low-lying Muskeget is best seen from the air.

Both islands are off-limits to visitors, fiercely protected by their

residents.

In the case of Muskeget, the defenders are gray seals that have

established

a large breeding colony on the island. Tuckernuck’s defenders are

its

property owners, who occupy the island’s scattering of houses.

There

is no public land on the island, not even the beaches.

The fact that one needs an invitation to visit

Tuckernuck

has endowed the place with mystique. Most people who have lived

their

entire lives on Nantucket have never set foot on its shores, and those

who

have treasure the experience inordinately. People who have

inherited

property there constitute a minor aristocracy.

Tiny as Tuckernuck is, it is no stranger to

factionalism.

Wampanoags from both Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard traditionally

retired

to the island for fall duck hunting, and they also buried their dead

there.

Then, starting in the late 1600s, English settlers let livestock loose

on

the island. For a while in the early 1700s a little gang of

Wampanoag

sheep rustlers preyed on the introduced animals, but in a short time

the

Wampanoags’ traditional hunting land had been lost to the English, who

took

the island over for farming.

Bigelow House on Tuckernuck.

courtesy Nantucket Historical Assn

By 1800 Tuckernuck was sustaining forty cows, while

between

eight hundred and a thousand sheep were cropping the fragile vegetation

to

the roots. Environmental degradation and rising sea levels have

since

joined forces to markedly reduce the area of Tuckernuck, and in the

process

to expose ancient burials that were intended for eternity.

There are no longer any year-round Tuckernuck

residents,

but until the twentieth century old settler families such as the

Tuckernuck

Dunhams and Coffins subsisted by farming, hunting, and fishing, while

their

children received basic education in the Tuckernuck School. Old

Tuckernuckers

were a close-knit society of cousins.

Enter yet a new group. Seasonal hunting

remained

excellent on both Tuckernuck and Muskeget, and in the late 1800s groups

of

recreational hunters from the mainland acquired land for

themselves.

Gradually their hunting camps and blinds evolved into retreats for

Boston

Brahmins and their friends. This was a privileged male society,

as

different as could be from the farm folk they were moving in on.

Each

side regarded the other as exotic.

At the beginning of the 1880s Henry Jacob

Bigelow,

son of Jacob Bigelow—botanist, surgeon, and Harvard Medical

School

professor—had a house built for himself on the western shore of

Tuckernuck.

A physician like his father, Henry Jacob was a surgeon and a pioneer in

the

use of surgical anesthetic. It was taken for granted that

medicine

would be the family profession, passed on from generation to

generation.

Henry had just one child, a son named William Sturgis Bigelow.

William’s

mother died when he was still a child, and although he pleased his

father

by becoming a crack shot who could drop birds out of the sky with the

best

of them, his nature rebelled against the practice of medicine.

Having

earned a medical degree, he took off on an extended tour of Europe, not

returning

to Boston till he was 29. Two years later he escaped again by

accompanying

Harvard professor Edward S. Morse to Japan. Staying on for eight

years,

William Sturgis Bigelow studied Japanese culture, collected Japanese

art,

converted to Buddhism, and was decorated by the Emperor of Japan with

the

Order of the Rising Sun.

William Bigelow’s library on Tuckernuck,

courtesy Nantucket Historical Assn

By now it was clear that this Bigelow would never

practice

medicine, nor would he give his father a grandson to carry on the

family

name and profession. Instead, he became a lecturer on Buddhism

and

Japanese culture at Harvard and cultivated a circle of men

friends.

Among them were Brooks Adams; Henry Adams, who married Bigelow’s first

cousin;

Senator Henry Cabot Lodge and his son, who was known as “Bey” Lodge;

John

LaFarge; and Theodore Roosevelt. Edith Wharton would have liked

to

be part of their group, but finding herself excluded, she contented

herself

with sniping from the sidelines. Of Bigelow she remarked acidly

that

‘his erudition far exceeded his mental capacity.”

All the men in Bigelow’s circle dabbled in

Buddhism,

and much of the dabbling took place during summers at the Bigelow house

on

Tuckernuck. There Bigelow amassed a library of three thousand

volumes,

many in French and German, and some reportedly racy. Some were

rare

old volumes, and some were publications by Bigleows of past

generations.

Part of the collection dealt with the spiritual and the occult, and

also

included were French cartoon books poking fun at human nature.

Visitors

to Bigelow’s Tuckernuck retreat were welcome to spend the day

discussing

metaphysics in their pajamas, while Bigelow himself favored his

Japanese

kimono. For breaks from intellectualizing, there was a waterside

tennis

court and a Japanese bath. Women were absolutely banned, and

skinny-dipping

was encouraged. From sweltering mid-summer Washington, D.C.

Senator

Lodge wrote of his impending visit to Tuckernuck, “Surf, Sir! And sun,

Sir!

And Nakedness! Oh Lord, how I want to get my clothes off!”

Bigelow’s only house rule was that his guests had

to

dress for dinner. He set a good table with excellent food (often

fresh-caught

bluefish) and fine wine.

During these summers, Bigelow kept a journal that

he

called "Notes on the Universe and Kindred Topics as Seen from

Tuckernuck.”

Then a pair of misfortunes cast a shadow over Bigelow’s off-shore

idyll.

A friend named Trumbell Stickney died suddenly on the eve of a trip to

the

island, and in the summer of 1909, Bey Lodge suffered a seizure and

died

on Tuckernuck. Both were young men in their thirties. As

Bigelow

brooded over these losses, the encroaching sea took a bite out of the

corner

of his tennis court. Sensing that his house was now haunted,

Bigelow

abandoned Tuckernuck.

Upon his death, fifteen years after that of Bey

Lodge,

Bigelow was cremated. Half of his ashes were interred in the

Mount

Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, and the other half were carried to Japan

and

interred by a Buddhist temple in Kyoto. His superb art collection

became

a cornerstone of the Asian collection of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

The eroding shore continued to creep ever closer to

the

Bigelow house on Tuckernuck, and at the end of the 1930s it was partly

demolished

and partly moved to the other side of the island, where it was

incorporated

into the LaFarge family house. The rarest and best of Bigelow’s

books

had been taken to the mainland, but the rest remain on Tuckernuck with

the

LaFarge family.

Bigelow’s Tuckernuck journal is now part of the

manuscript

collection of the Nantucket Historical Association.

From: Professor Grzegorz RACKI <

grzegorz.racki@us.edu.pl >

Because of my historical/geological research, I would be grateful for your help in the query referred directly to the XIX century Bigelow family from Boston. There are two quotes of totally forgotten scientific paper: