Horace Holly 8 BIGELOW

Page 3

Forge "The Bigelow Society Quarterly; April &

July 1991; vol 30, no 2 & 3

Horace Holly 8 BIGELOW

"THE RINKMASTER" (Part I)

15182.429 Horace Holly 8 BIGELOW,

son of Levi 7 ( Gershom

6 , Ivory 5 ,

Gershom 4, John 3, Samuel 2, John 1)

Although there are still folks around who remember White City at Lake Quinsigamond,

few recall it in its original splendor, After World War II, White City was

only a shabby shadow of its former self, an aging dowager done in by time.

It finally closed in 1961. Lincoln Park, on the Worcester side of the lake,

had already succumbed to changing fashions.

In its glory days, though, White City was the centerpiece of the greatest

public entertainment complex in Worcester's history. From about 1890 to 1940,

Lake Quinsigamond was the magnet for Worcester County fun lovers and thrill

seekers.

By streetcar and by the tens of thousands, they came to ride the rides,

to see the hawkers, to enjoy the fireworks displays, the waterslides, the

lake steamers, the diving ponies, the canoes and rowboats, the lively midways,

the band concerts and the moving throngs. No one knows how many visited the

lake over the decades, but they surely numbered in the millions.

It was not always so. In the real old days, the lake was for the classes,

not the masses. Harvard, Yale and Brown began holding their sculling races

there in 1859. Elegant hotels, summer estates and yachting clubs appeared

along the shore after the Civil War. Until 1873, the workers living in three-deckers

in the Island or on Vernon Hill had no way to get to the lake except by foot.

For a family with six or eight children, the two and one half miles might

as well have been 50. According to one account, an average weekend at the

lake in 1870 would find not more than 150 visitors.

Who changed all that? Who opened up the lake to the people? Who brought

mass entertainment and recreation to Worcester? Who cracked open the Sunday

Laws for the benefit of the working class? Who did the most to Americanize

the polyglot Worcester population?

Meet Horace Holly BIGELOW, populist-capitalist, entrepreneur extraordinary,

friend of the working man and an enigmatic eccentric touched with genius.

He was born 2 June 1827, at Marlborough, MA. Early on he went to work in

his father's shoe shop, where everything was done by hand. By the time he

was 20, he was inventing one shoe machine after another, including the heel

pressing and nailing machines, from which he deservedly won a large fortune.

By the time he was 30, he had largely mechanized the shoe industry and was

being hired by New York and other states to set up shoe factories using convict

labor.

When the Civil War came, Horace organized shoe production for the government

at the state prison in Trenton. NJ, and turned out uncounted thousands of

shoes for the Union Army. He came back to Worcester in 1863 and set up the

Bay State Shoe Co. on Austin Street. In 1873, he exhibited some of his shoe-making

machinery at the Vienna Exposition, where crowds including Emperor Franz

Joseph gaped at the sight of a pair of shoes being turned out every five

minutes.

For all the splash he made in Europe, Horace was somewhat suspect back

in Worcester. Despite his wealth and Yankee background, he was never an establishment

insider. Some of his ideas raised eyebrows. Sunday concerts, for one. Entertainment

for the ordinary people, for another, electricity, for a third. Old Horace

was a real nut about electricity. He said, back there in the 1880s, that

it was going to revolutionize American life and industry.

Then there was his scheme for profit-sharing, which he announced in 1867

for his shoe company employees. Back then such notions were unsettling to

some manufacturers. In 1878, the R.G. Dun & Company credit report called

BIGELOW "a keen, shrewd businessman, but not well regarded socially

in some quarters." In 1882, the Dun report referred to him as someone who

is "regarded as a peculiar man of radical ideas in politics and religion,

which make him rather unpopular."

That was three years after Horace ran for mayor of Worcester - as a Democrat.

Highly irregular, some thought. Although in those days there were many Yankee

Democrats, Horace shook some important applecarts. For years Stephen SALISBURY

and the establishment had worked out a cozy arrangement with the leading

ethnic politicians to install various "citizens party" candidates to run

things at City Hall. Horace looked like a risky maverick to both sides. Deals

were made, and Horace lost the election, despite his popularity with the

working class.

The political setbacks and official disapproval did not stop Horace for

a minute. With Worcester's population doubling every 15 years, he was convinced

that vast opportunities lay open to whomever could offer cheap, healthy recreation

to the working class.

His first insight came in 1873, when he and other prominent men invested

in J.D. COBURN'S "Dummy Railroad"-so called from the odd shape of its first

locomotive. It ran from Union Station to Lake Park. Its narrow-gauge track

paralleled the Boston and Albany tracks along East Worcester Street. to Bloomingdale,

swung off toward the east, looped around near Anna Street and terminated

at Belmont Street at the lake. A turntable reversed the locomotive for the

return trip. The fare was a dime. Within months, the Dummy was carrying more

than 1,300 passengers a day on weekends, and Lake Quinsigamond was becoming

the mecca for the masses.

COBURN had built the railroad mainly to brlng more customers to his lakeside

hotel. Horace had a grander vision. He sold his shoe business, bought out

COBURN and the others in 1883, and set about developing the lake as the premier

recreation place for the masses.

It took him only a few years. In 1884, he and Edward L. DAVIS donated 100

acres to the city of Worcester for Lake Park, still one of the community's

finest. On July 4, 1885, he sponsored a big boating regatta that attracted

an estimated 20,000 people.

They taxed the Dummy Railroad to the limit. By that time, the Dummy was

hauling four open cars, each seating 60. According to one account. "Seats

were of the iron-frame wood-slat design and well served their purpose. However,

the end of the route usually found the occupant willing enough to get to

his feet and leave the hard seat for the next victim." Heading back to the

city with four fully-loaded cars, the engine sometimes had to stop and build

up steam before chugging up the steep grade near Anna Street. Horace sold

the Dummy to the street car company in 1892.

After that, people rode to the lake on the new trolley cars. The figures

tell the story. Average weekend attendance at the lake jumped from about 150

in 1870 to an estimated 20,000 in 1890.

Horace Holly 8 BIGELOW

"THE RINKMASTER" (Part II)

15182.429 Horace Holly 8 BIGELOW,

son of Levi 7 ( Gershom

6 , Ivory 5 ,

Gershom 4, John 3, Samuel 2, John 1)

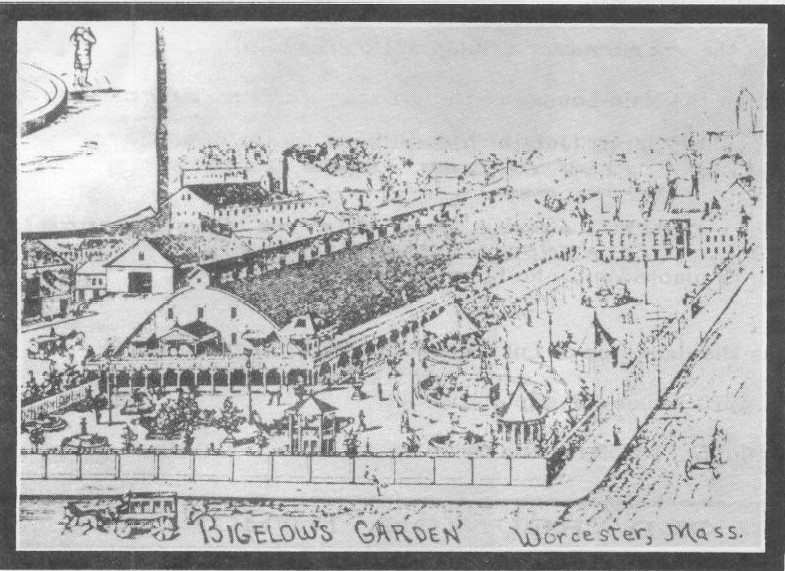

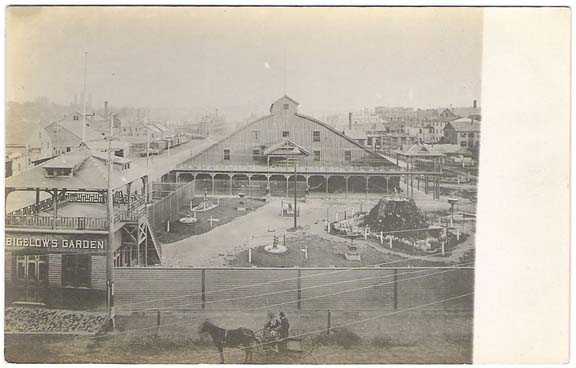

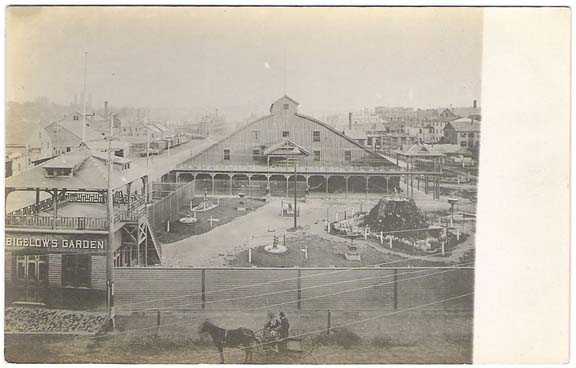

Photo above of Bigelow's Garden supplied by Don Bigelow of Bradenton,

Florida

Don is a direct descendant of Horace Holly and states: "A

careful look at the mound to the right of center will show a person is on

top.

This was "Mount Vesuvius" an electric light show that was way ahead of its

time."

Lake Quinsigamond was only one of Horaces's interest. In 1878, the LALIME

brothers from Canada had built "THE RINK", a cavernous wooden building

between Foster and Mechanic streets, designed for roller skating. The LALIMES

hoped to attract only the better sort. They excluded "the rabble." Blacks,

among others, were

not welcome. By 1881, the RINK, for all its popularity, was

in financial straits. Horace bought out the LALIMES that year and promptly

cut roller skating prices by a third. He excluded no one. Roller skating quickly

became a Worcester craze, with thousands propelling themselves around the

hardwood floor. He bought five other roller skating rinks in other cities

and quickly made them profitable.

In Worcester, he added an outdoor swimming pool, fountains and concessions,

all surrounded by a tasteful wooden fence. Horace's Garden fronted on Norwich

Street and covered the whole block between Foster and Mechanic Streets. Thousands

thronged through its portals each week to disport themselves and to watch

various events, from six-day bicycle races to comic operas.

On July 23, 1882, a Sunday, Horace put on an open-air concert at BIGELOW'S

Garden. Proper types were aghast at this flouting of the blue laws. Union

Church, then located on Front Street, complained to City Hall. Horace insisting

that he had as much right to run his entertainment business as druggists had

to sell cigars, and announced that a second concert would be held the following

Sunday. That concert started off with two religious numbers, but was then

closed down by the police. Horace was hauled into court.

He lost the case, was fined $20 and appealed to Superior Court. His trials

gave him a marvelous opportunity to stand up for the right of working people

to enjoy themselves on the sabbath. It was no worse, Horace maintained, for

a poor man to ride a wooden horse on Sunday than for a rich man to drive

a real horse. Finally, after his appeal to the Supreme Judicial Court, the

city decided not to press the case. By that time, 1884, Sunday was the biggest

day at Lake Park and Lake Quinsigamond.

Although he was deeply involved in public recreation, both at the lake

and at the Rink, Horace found time to promote a new interest-electricity.

Convinced that electric power was the road to the future, he installed a

generating plant to illuminate the Rink by arc light. That was in 1883, a

year before the Worcester Electric Light Co. began operations.

Electric power expanded in Worcester, but much too slowly for Horace. In

1887, he held a mammoth electrical exposition at the Rink, with 140 exhibitors.

Gov. Oliver Ames was there to pull the switch that set 140 lights a-blazing.

A crush of people gawked at the spectacle of the industrial exhibits, all

driven by electricity. An electric street car moved back and forth on special

tracks, sparks flashing from its wheels.

Horace saw the exhibition as a way to educate the masses. He told a Telegram

reporter, "Every man, woman and child in Worcester able to do so will have

an opportunity to visit the electrical exhibition at the rink before it closes.

If they are too poor to buy a ticket, I will give them one; poverty shall

not debar anyone from attending it if they want to."

Four years later, Horace staged another spectacular electrical exhibition

at the Rink. By then, electricity was well established, and Horace returned

to his first interest; popular entertainment and recreation. Although the

Rink's popularity declined after the roller-skating craze ran its course,

the BIGELOW operations at Lake Quinsigamond were expanded and drew ever larger

crowds.

Catering to the masses had its problems. On April 30, 1877, the Gazette

published a letter from Charles F. WASHBURN and Philip L. MOEN deploring the

sale of "intoxicating drinks" at the lake in "utter disregard and desecration

of the New England Sabbath." In 1885, the pro-labor Worcester Star criticized

the "drunkenness and rowdyism" of the crowds at the lake. Things didn't improve,

either. In 1907, after Horace opened White City, a headline in the Gazette

announced "VICE AND CRIME RUN RIOT AT LAKE." The story said that "the atmosphere

reeks with rottenness and pollution, which is fast driving away respectable

people and giving this beauty spot to the wicked, lawless and ignorant."

Horace, a temperance man, did not allow liquor to be sold either at the

Rink or at Lincoln Park. However, others were more than willing to satisfy

the thirsty crowd. A famed refreshment spot was William Bioss' Island House

on Ramshorn Island, which was connected to Lincoln Park by a convenient wooden

bridge. There were other such spas, some on the Shrewsbury side. By all accounts,

the old days at the lake were lively. On some weekends, the crowds probably

topped 50,000. Under Horace's guidance, Lake Quinsigamond became a powerful

force in the Americanization of Worcester's polyglot population. Young people

swarmed out of their various ghettoes and ethnic enclaves to mingle together

on a level of equality. All sorts of barriers tumbled as people splashed

each other on the beaches, took evening cruises on the excursion steamers,

rented J.J. COBURN'S canoes and rowboats (he had more than 200), and dared

the rides and thrills of Lincoln Park.

The demand for lake recreation kept growing as the population increased.

With the Worcester side pretty much developed, Horace looked across the water

to the largely unspoiled Shrewsbury shore. He bought a large piece of land,

named it White City and began to put in the finest amusement park that money

could buy, modeled after Coney Island.

It opened in 1905, when Horace was 78 years old, and was wildly popular

from the start. On its first Sunday, 30,000 people paid their dimes to enter

its gates. They found it every bit as magical as the crowds today find Disney

World. It had spectacular rides, a roller coaster, a waterslide, a Tunnel

of Love, hawkers of all sorts, fireworks at night and a whole gamut of entertainments.

For decades it was Worcester County's favorite entertainment spa. There is

little sign of the old magic today, in the rather plain shopping center with

the White City name, far removed from the excitement and crowds of yesteryear.

Horace died in 1911, controversial to the last. The Telegram obituary recalled

the time when he had hired Thomas H. DODGE a prominent lawyer, to represent

him in a legal matter. DODGE charged him $25,000. After the trial, Horace

found out that the other side had paid their lawyer only $2,000, so he hired

George Frisbie HOAR to represent him in a suit against DODGE for excessive

charges. He eventually recovered several thousand dollars.

In his fine book on Worcester labor and working-class recreation, Eight

hours for What We Will, Roy ROZENZWEIG can't make up his mind

whether Horace was a true populist reformer or just a shrewd operator. Horace

doesn't quite fit the pattern for ROZENZWEIG'S thesis of class conflict: he

was always straying off the reservation. However, ROZENZWEIG notes that Horace

became a wealthy man by catering to the masses.

True enough. But, according to the Telegram obituary, Horace could have

become far wealthier if he had patented more of his shoe machinery inventions.

He took the attitude that such improvements should go for the welfare of everyone.

His profit-sharing scheme and his insistence on low admission prices were

other examples of his eagerness to improve the condition of the working class.

Unlike some successful men who started out as poor boys, he never seemed

to forget his origins.

Whatever Horace's motives were, Worcester can feel thankful for him. Although

White City and Lincoln Park are only memories, Lake Park survives. It will

serve as a fitting monument to his life and career.

.

Sources:

WORCESTER MONTHLY June 1989 Article by Aibert B. SOUTHWICK

Horace Holly page 1

Horace Holly page 2 = Howe, Bigelow Family

of America; p 412 ;

also see:

http://bigelowsociety.com/Horace_Holly_Bigelow.html

Modified - 12/28/2002

(c) Copyright 2002 Bigelow Society, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rod Bigelow - Director

< rodbigelow@netzero.net >

Rod Bigelow (Roger Jon12 BIGELOW)

P.O. Box 13 Chazy Lake

Dannemora, N.Y. 12929

< rodbigelow@netzero.net >

< rodbigelow@netzero.net >

BACK TO THE BIGELOW

SOCIETY PAGE

BACK TO BIGELOW HOME

PAGE