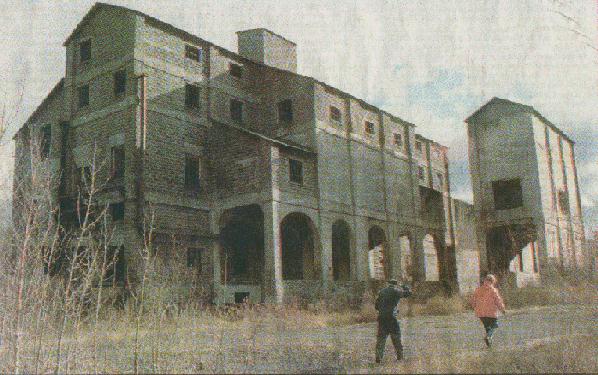

This is the Power House in Lyon Mountain, as it looks today.

Tony Shusda remembers his first day of work in 1936 at the Lyon Mountain mines. He was 21.

"If you had boys in your family and your

father got killed or something, or if they were old enough to work and

lived in that house, the boys worked," he recalled. "If you didn't,

you were out." He also remembers his last day of work at the mines

in 1967, hoping he could make history "I wanted to be the last one to

punch out, but wasn't," he laughed. Second to last would have to do.

Few could match Shusda's intricate knowledge of the iron mining industry,

an industry that spanned the mid 1800s to 1971 when the last of the great

area mines closed in Moriah. And the impact of mining forever changed the

North Country. Shusda, one of many whose job was to dig in rock deep in

the bowels of the Earth, hoist it up and push it through the mill, talks

about mining as if it happened yesterday. "We worked five days a week;

during the war, seven."

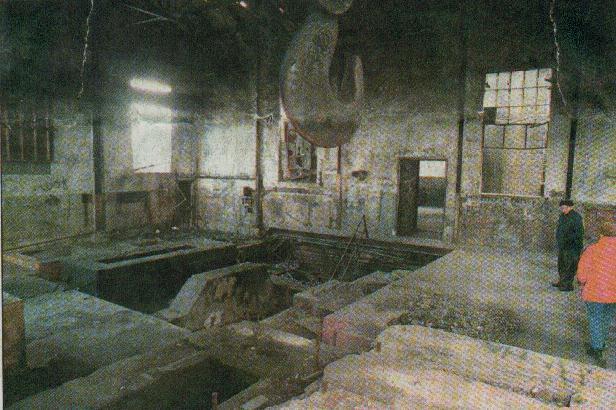

There was the Power House with a boiler

room and five compressors (all eventually wound up equipment at ski

areas); the machine-shop fire when the water froze in the 25-below temperatures,

before it could douse the blaze. He remembers the pond that doubled as

swimming hole and a source used to cool the compressors, and he remembers

the day Archie Hart died in that swimming hole. He also recalls, still

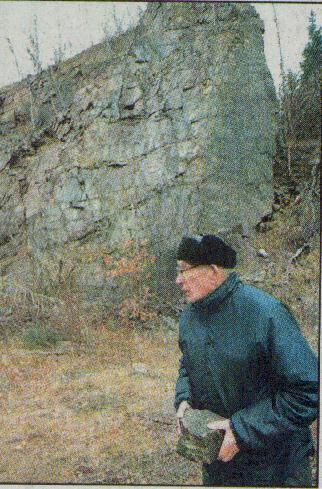

with a feeling of sadness, a fateful day in 1940. "My father was killed

in the mine," he says shaking his hand at one of several gaping holes

in the Lyon Mountain landscape. "He went to blast a couple boulders

that were caught, and he got pinned. The guys he was working with just

took off and left him there. He suffocated. It was dangerous," Shusda

said matter-of-factly but "it was a job"

Dr. John Moravek, coordinator of the Geography

Department at Plattsburgh State said the abundance of iron ore was the

reason mining became the lifeblood of dozens of local communities for more

than 100 years. Iron ore was, and still is, concentrated in only few regions,

including the Adirondack-Lake Champlain region. Thousands of tons of iron

ore came from the belly of Adirondack mines to go through crushers, concentrating

plants and furnaces, headed for distant factories to be made into nails,

rolled iron, stoves, machinery, tools railroad track and steel beams that

built a nation. Transportation, mainly by railroad, was critical to every

mining community. Towns with accompanying stores, schools, barbershops

and bars -- grew, developed and revolved around the mines.

Tahawus (Native American for "cloud splitter"),

at the head waters of the Hudson River 40 miles west of Lake Champlain

was once a growing village in the shadow of mining operations.Some impurity

had been found in the Adirondack (later Tahawus) iron that made it unusable

in the 1850s. That by-product was titanium.With obstacles that included

a financial panic and inaccessibility, isolation, difficult transportation

and severity of climate, titanium couldn't be mined, and Adirondac became

a ghost town. In 1941, the National Lead co. (which eventually acquired

Repubic Steel), realizing the country's need for the strategic war mineral

in World War II, began mining titanium. Then, because of the needs of expansion

in 1963, the entire village of Tahawus was moved -- lock, stock and barrel

-- to Newcomb, 12 miles away.

Jack "Sparky" Brennan, an electrical engineer

for Republic Steel in Moriah, knows well what mining towns went through

to keep the business going. Republic Steel arrived in the North Country

in the 1930's. The company came in, upgraded and modernized equipment and

made the job safer. Brennan's memories are of decades of hard work in a

"boom town." With almost 100 mines in the Town of Moriah alone, mining

became a very profitable venture. The "21 Pit", just south of Mineville,

was one of the most productive and prosperous. "It followed two veins

of ore 200 to 800 feet apart. Do you know how long it took for them to

connect when you can go eight feet a day?"

Brennan, too, recalls events surrounding

mining with great ease. He remembers that women did not work in the mines

or the plant, only in the office and warehouse. He recalls the tragedy

in 1951 that claimed the lives of three men but increased safety with the

installation of steel beams in the mines. He can also remember his great

uncle Jim Brennan, who was in a brawl. "That man was shot in the stomach,

fell in a shaft, (was) carried out, walked in his house and died",

Brennan said.

But years of mining deeper and deeper into

the ground proved to be the nail in the coffin of the north Country's iron

industry. "The cost of just getting the iron ore to the light of day

became prohibitive", Moravek said. "It simply reached a point where

the mining operations were no longer profitable, and Cleveland (the

home of National Lead) pulled the plug." He said it was a shock

to the townspeople who depended on Republic Steel. "North Country residents

were caught off guard when the announcement came that they were closing

the mines."

The Lyon Mountain mines closed in 1967;

the Moriah mines followed suit in 1971. "There are now many low-cost

alternatives to iron, including recycling. To re-open, (the mining

companies) would have to comply with the extensive rules of the Adirondack

Park Agency and Department of Environmental Conservation." Moravek

said there's plenty of iron ore left in the North Country, "more

than what has ever been removed. Re-opening the mines is not unthinkable,

but very remote. I can't forsee circumstances that would prompt a revival.

It's a matter of supply, demand and profitability." He said the expense

of re-development seems extremely prohibitive, and, besides, there are

so many low-cost alternatives. "Why would anyone come back here?"

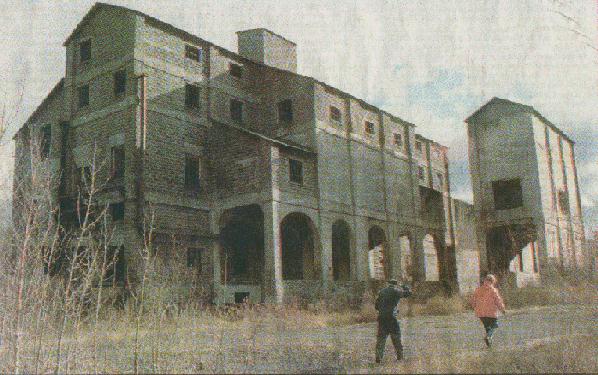

North Country mines, long abandoned,

are now home to thousands of bats and other assorted creatures. Echoes

of the past ripple through the accompanying dilapidated buildings. Brennan

is a guest speaker for area organizations and the source of knowledge for

the Iron Center, a former carriage-house-turned-museum near the Town Hall

in Port Henry. Shusda moved to Plattsburgh State, where he worked in security

at the college and then the bookstore. Except for the occasional rmble

of town trucks, a dead silence now prevails at the Lyon Mountain mines.

That's OK as far as Shusda is concerned. There's one word to describe the

best part of his experience working in the mines. "NOTHING".

Sources:

Mining History page;

Plattsburgh Press Republican; Jan. 3, 1999;

article by Louise Spring, Photos by Dave Paczak.

Also see:

Lyon Mountain page 1.

Lyon Mountain page 2.

Lyon Mountain page 3.