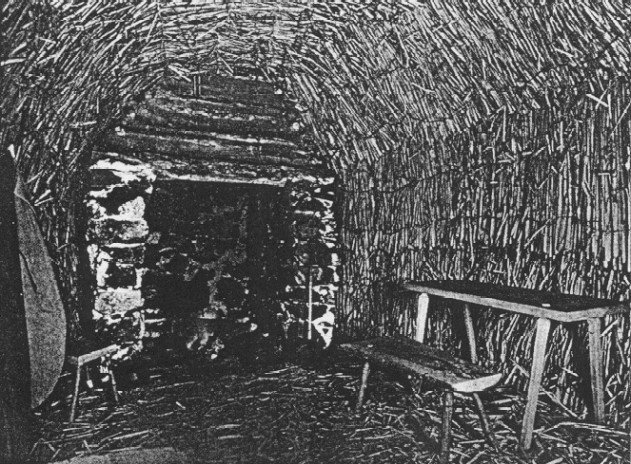

Interior of an English Wigwam

Thatch as a roof covering has been alluded to.

This was common in the early days. Notwithstanding the fact that the Great

and General Court forbade its use, it still persisted as necessity arose.

At the outset, towns along the coastline would set aside certain parts of

thatch banks in the marshes, as a supply for thatching houses. Rye straw

also was much used for thatching and has been used in thatching the roofs

of the cottages in the present colonial village. The roofs of these thatched

houses are not boarded as the thatch is fastened to slats.

The earliest frame houses were covered with weatherboarding

and this before long was covered with clapboards. The walls inside were sheathed

up with boards moulded at the edges in an ornamental manner and the intervening

space was filled with clay and chopped straw, and later with imperfect bricks.

This was done for warmth, and was known as "nogging," following the English

practice. When roofs were not thatched, they were covered with shingles split

from the log by means of a "frow" and afterwards hand-shaved. The window

openings were small and were closed by hinged casements, just as the houses

in England were equipped at that time. Generally, the casement sash was wood,

but sometimes iron was used, as was common in England.

The glass was usually diamond- shaped, set in lead

"cames." Emigrants to New England were instructed by the Company to bring

ample supplies of glass for windows, but the supply ran short and in the

poorer cottages and wigwams, oiled paper was in common use. This was an excellent

substitute and supplied a surprisingly large amount of light, as may be noticed

in the present wigwams.

A brickyard was in operation in Salem as early as

1629, and everywhere along the coast clay was found and made up into bricks.

Bricks in small quantity may have been brought from abroad as ballast in

ships, but it is safe to say that nearly all the chimneys were built with

bricks made near at hand. Chimneys were built upon a huge stone foundation.

The brick work began at the first floor level and the bricks were laid in

puddled clay up to about the ridge line where lime was used as the chimney

top became exposed to the weather.

The furnishings of these houses were very crude.

Only a few pieces of furniture,such as oak chairs and chests, were brought

from England. The emigrant carpenter or cabinetmaker made up tables, stools,

and beds as occasion demanded.

One of the first estates probated in the county was

that of the widow Sarah Dillingham of Ipswich, who died in 1636. It amounted

to £385, a goodly total for those days. Her kitchen was well equipped

with all manner of utensils and plenty of tablecloths and napkins, but there

were no curtains at the windows, and a table, chair, or stool is not listed

in connection with the kitchen. There were cushions, and probably the simplest

kind of furniture sufficed. Stools, chests, and table boards were in use;

bedsteads were low; and many pallet beds were made up on the floor. There

were no carpets on the floor nor pictures or other decorations on the walls.

Kitchen sinks were unknown and water was brought into the house in wooden

buckets from the spring or well. These early houses had no closets and clothing

was kept in chests and boxes.

The site of this Colonial Village at Salem is directly

on the harbor and when selected was barren of trees and shrubs -a piece of

undeveloped park land. A pond was excavated and a shore line constructed

from surplus material. A spring was located in a depression in the hillside

and from it a brooklet flows down tot he pond. Several hundred boulders were

brought and placed in suitable locations, especially along the line of the

brook, and over two thousand native trees, stumps, shrubs, and vines were

planted to give the Village the natural setting that it deserved. About the

governor's "fayre house" is a garden filled with herbs and flowers. Elsewhere,

tobacco and common vegetables are growing. The stocks and whipping post stand

in the village street and at various locations may be seen dug-out shelters

for animals, a saw pit, fish flakes, a blacksmith's shop, and apparatus for

making lye, and evaporating salt. Seldom has reproduction of the past been

carried out with such fidelity and with such success. The entire project

reflects the greatest credit upon all concerned and proved to be an outstanding

feature of the tercentenary year. The attendance was large and, public school

authorities at once recognizing its educational importance, it has been decided

to preserve the Village for the future and keep it open to visitors with

an admission charge to help maintain the up-keep.

English Wigwams, First two

Covered with Bark

Continued on Page 4. and Hathaway House.

Back to Page 1.

Back to Winthrop Fleet and John 1

Bigelow.

Back to Winthrop History

Information on these pages provided by:

Gerald G. Johnson, Ph.D.

648 Salem Heights Avenue, So.

Salem, OR 97302-5613

![]()