What remained of Bertha, a hurricane when it came ashore in North Carolina,

had just passed through Connecticut - unloading a July's worth of rain

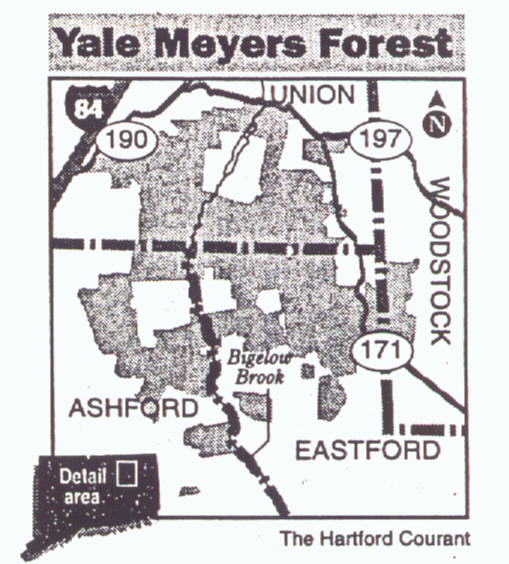

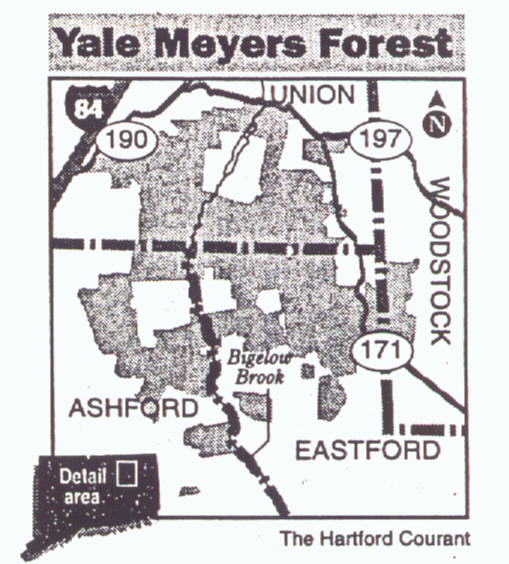

in a day. The streams were nearly out of their banks. Bigelow Brook, which

roughly bisects the Yale Meyers Forest, was a slow-moving, mostly shallow

stream last month, almost relaxed. A spotted sandpiper poked about on its

muddy fringe. In some of the marshy sections, bullhead lilies - their flowers

like tight fists - began to unfurl their intensely yellow flowers. Now

there was no muddy edge, and some of the lilies were underwater, pulled

down by the force of the brook - a brook with urgent work to do, moving

water. The forest had changed, not so much because of the storm - the storm's

effects were mostly fleeting, really -but by the cycle of the seasons.

It is mid-summer and the forest is determinedly going about its business.

The paradox of the forest is that it seems permanent' so finished -

but it is, in fact, dynamic and growing. Yale University estimates that

it could cut 100 board feet of timber - 1 inch thick by 12 inches wide

- from every acre of this forest, every year, forever, without harm. Henry

David Thoreau loved paradox, and Thoreau was on my mind. I had just returned

from Concord, Mass., and a meeting of the Thoreau Society, a

gathering of Thoreau scholars and devotees. At sunup, I revisited the

site of Thoreau's cabin on Walden Pond, then drove here...

Students at the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies,

who work in the forest during the summer and live in a pair of bunkhouses

about a mile from my camp, have discovered a baby porcupine and are keeping

an eye on it. During the day, it perches in the crotch of a quaking aspen,

an aptly named tree whose leaves tremble with but a whisper of a breeze.

On at least two occasions Thoreau took what he called "a fluvial

walk." That is, he took a walk in a river. "Divesting yourself of all your

clothing but your shin and hat, which are to protect exposed parts from

the sun, you are prepared for the fluvial excursion," he wrote. "You choose

what depths you like, tucking your toga higher or lower, as you take the

deep middle of the road or the shallow sidewalks."

Before me was Bigelow Brook, clear, deeper than it had been in weeks.

The day was hot, as it was on July 10, 1352, when Thoreau took one of his

fluvial walks, inspecting the bottom of the Assabet with his toes.

"I wonder if any Roman emperor ever indulged in such luxury as this

- of walking up and down a river in torrid weather with only a hat to shade

the head," he mused. In I went, wearing bathing suit and sneakers, no hat.

it was slow going. Move too quickly over the rocks, and, whoops. Nicked

the left ankle on that rock. Mud bottom here. Sand now. Rocks again. Up

to my armpits in water, I stumble over another rock and sag forward,

almost like slow motion, wetting the notebook I held aloft, like Thoreau's

toga. The ink began to run. what patience Thoreau had. I see him moving

ever so slowly, carehilly, taking in the landscape at water level, comfortable.

He doesn't fall. He sees everything.

I'm going too fast...The brook has opened to a small pool, maybe

25 feet long by 15 feet wide, as much as 5 feet deep. A sheet of cold water

issuing from a spring slides over a ledge that is the west bank of the

brook. The bottom is sandy, illuminated by a swath of sunlight that found

its way through hemlock boughs. A fluvial walk had become something less

eccentric, a swim, a private celebration of summer that lasted much of

a half-hour.

The water was cool, probably chilled slightly by the rain. The brooks

are like the arteries of the forest, and this artery ran remarkably clear,

the system acting as it was meant to. The trees and shrubs and plants that

cover almost every inch of the landscape were doing their part, taking

in some of the storm water as it fell, the soil acting as a filter. Along

the roads through the forest, in the marshy areas, and in places along

the brook, is a wildflower called tall meadow me, in full bloom. A month

ago you wouldn't have known it existed here. Now it, too, celebrated summer,

not 20 feet from my swimming hole.

Meadow rue is tall, up to 7 feet, though usually less. Wildflowers

its size sometimes have leaves the size of maples, flowers the size of

plums. The meadow rue, though, has delicate little leaves, an inch or two

long, with rounded lobes. The flowers, white and

massed in a plume at the top of the plant, are a fireworks display,

the stamens of each flower forming a starburst pattern.But instead of the

black of night as a backdrop for the rue, there are the infinite greens

of forest, marsh and meadow.

Contributed by Laura Edwards, Ft Myers FL.

Should anyone know how Bigelow Brook received its name, please contact

me.

July 1998 FORGE:

The Bigelow Society Quarterly Vol 27, No.3 page 53