Katharine Bigelow 7 LAWRENCE

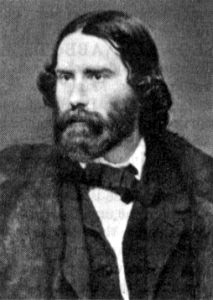

Katherine and son Percival (about August 1855)

16952.17 Katharine Bigelow 7

LAWRENCE, dau of Katharine 6

( Timothy 5 , Timothy 4 ,Daniel

3,Joshua2, John1) BIGELOW, and Hon.

Abbott LAWRENCE, was born 21 February 1832. She married 01

June 1854 Augustus Lowell, son of John Amory Lowell of

Boston. They had three sons

and four daughters, of whom five reached maturity. Best-known among

them

were:

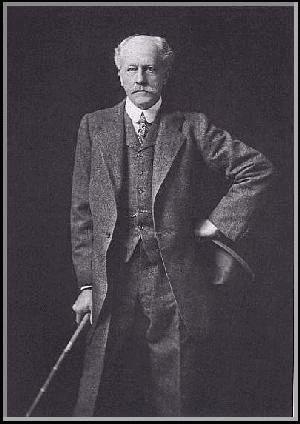

16952.17a Percival,

b 13 Mar 1855; d 13 Nov 1916; m Constance Savage Keith; he was a

prominent astronomer and founder of Lowell Observatory.

Lowell,

Percival (1855-1916), American astronomer, who made

significant observations of the planets. He is best known for his

belief that there are canals on the surface of Mars and that these

canals provide evidence for the existence of intelligent life there.

Born in Boston, Massachusetts, and educated at Harvard University,

Lowell traveled in Japan and Korea from 1877 until 1893 and later wrote

books about East Asia. In 1894 he founded and became director of the Lowell Observatory at Flagstaff,

Arizona. From 1902 until his death, he was nonresident professor of

astronomy at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He predicted

the discovery of Pluto, which astronomers first observed in 1930 at the

Lowell Observatory. Lowell's writings include Mars and Its Canals

(1906), Memoir on a Trans-Neptunian Planet (1915), and The Genesis of

the Planets (1916). Visit link for more

information, including:

The American astronomer Percival Lowell, b.

Boston, Mar. 13, 1855, d. Nov. 12, 1916, is best known for his belief

in the existence of artificial canals on MARS. Lowell was a businessman

and traveler in the Far East before becoming obsessed with Giovanni

Schiaparelli's report (1877) of canali ("channels") on Mars. He founded

(1894) the Lowell Observatory near Flagstaff, Ariz., especially for

studying the Martian

surface, and for more than a decade he charted the apparently

crisscross

markings of Mars.

Although

other astronomers vehemently denied the existence of canals on Mars,

Lowell maintained that not only did they exist, they had also been

built by intelligent beings. Not until the Mars probes of the 1960s

were Lowell's claims conclusively disproved. Despite the controversy

over the Martian canals, Lowell Observatory has contributed

substantially to studies of the planets and the stars.

Lowell himself predicted the position of a perturbing planet beyond

Neptune,

later discovered by Clyde Tombaugh, (b. Feb. 4, 1906 d. Jan. 17,1997)

and

named Pluto.

See more of Percival at the following LINK:

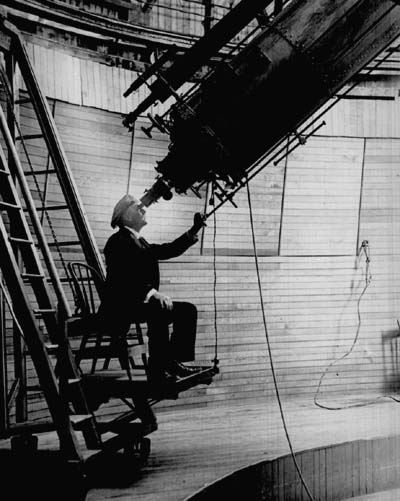

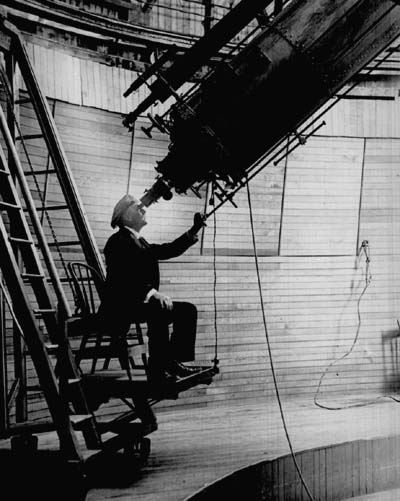

Percival Lowell (1855-1916) is one of the best known

observers of

the planet Mars. Lowell is pictured here in the observer's chair of the

61-centimeter

(24-inch) refracting telescope in the observatory he established in

Flagstaff,

Arizona. Lowell Observatory is still one of the foremost sites for

telescopic

studies of Mars and the other planets.

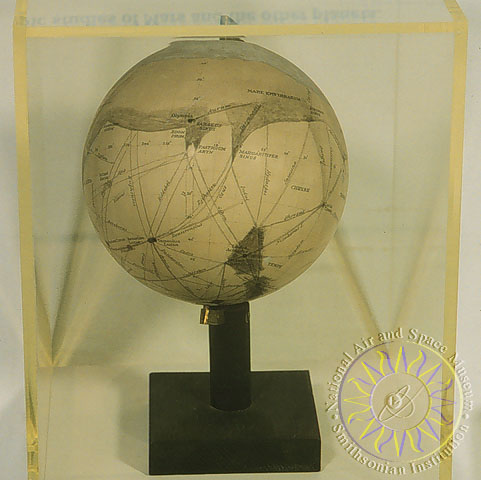

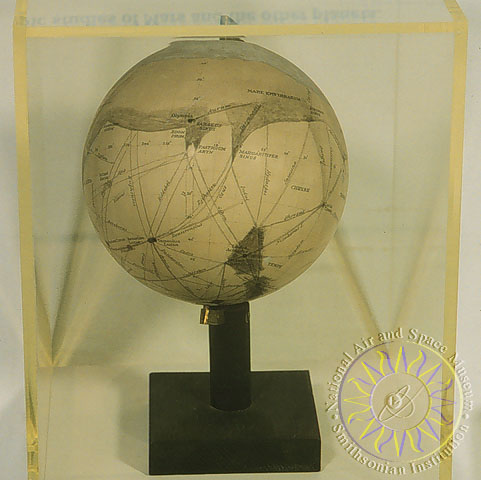

Percival Lowell made this globe of Mars summarizing his observations of

the planet for the year 1901.

The straight lines represent features that were first "seen" by the

Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli in 1877.

He called them canali, an Italian word meaning channels.

The canali were also observed by Lowell who concluded they were canals

built by intelligent beings.

The canals supposedly supplied water from the melting polar caps to a

desert world.

In his book "Mars as the Abode of Life", published in 1908, Percival

Lowell presented his theory that Mars' canals were built by intelligent

beings.

Today we know that there are no canals built by intelligent beings on

Mars and that Lowell was mistaken in his conclusions.

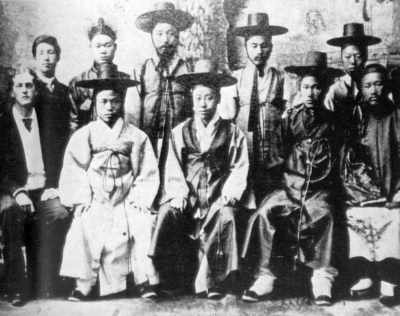

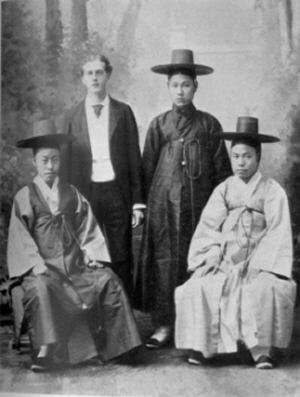

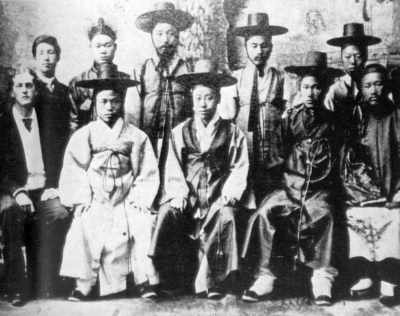

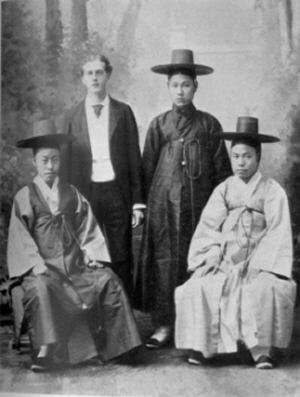

(above) A young Percival Lowell in Korea (ca 1883)

(above) A young Percival Lowell in Korea (ca 1883)

Percival

Percival

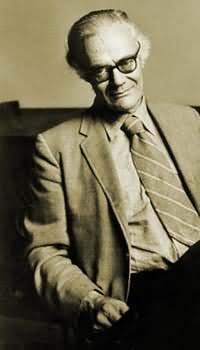

16952.17b. Abbott Lawrence Lowell,

was born 13 December 1856. He married in 1879 Anna Parker Lowell;

no issue. He was of M.I.T. and Lowell Institute, wrote with scholarship

on many subjects, was president of Harvard College 1909-1933, and known

for his educational reforms. He died 06 January 1943.

Lowell, Abbott Lawrence (1856-1943), American educator, born in

Boston, and educated at Harvard University and Harvard Law School. He

practiced law in Boston from 1880 to 1897, when he became a lecturer in

political

science at Harvard. He was appointed professor in 1900 and nine years

later

became president of the university. Among the administrative reforms he

introduced were general examinations given in their major subject to

candidates

for the baccalaureate degrees, the institution of the tutoring system

for

upperclassmen, and the establishment of a house plan, comprising

residential

units similar to those in British universities. In 1927 Lowell was

appointed

by Massachusetts Governor Alvin Tufts Fuller as a member of a committee

to advise the governor with regard to the Sacco-Vanzetti case. The

opinion

rendered by this committee was that the defendants had had a fair trial

and had been justly convicted. Lowell retired from the presidency of

Harvard

in 1933. He was a strong supporter of American participation in the

League

of Nations. His writings include Essays on Government (1889), Conflicts

of Principle (1932), and What a University President Has Learned (1938).

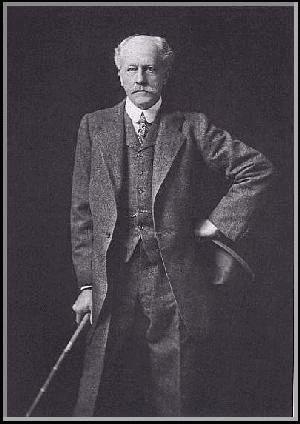

Percival and A. Lawrence Lowell

16952.17c. Amy Lawrence Lowell, was

born 09 February 1874 (the seventh child). She died 01 May 1925;

unmarried; educated Baylor, Columbia, and Tufts; in literature at Brown

and Yale;

well-known American poet.

Biography

Amy Lowell About the author:

From the notes to "The Second Book of Modern Verse" (1919, 1920),

edited by Jessie B. Rittenhouse.

Lowell, Amy. Born in Brookline, Mass., Feb. 9, 1874. Educated at

private schools. Author of "A Dome of Many-Coloured Glass", 1912;

"Sword Blades and Poppy Seed", 1914; "Men, Women and Ghosts", 1916;

"Can Grande's Castle", 1918; "Pictures of the Floating World", 1919.

Editor of the three successive collections of "Some Imagist Poets",

1915, '16, and '17, containing the early work of the "Imagist School"

of which Miss Lowell became the leader. This movement, . . . originated

in England, the idea have been first conceived by a young poet named T.

E. Hulme, but developed and put forth by Ezra Pound in an article

called "Don'ts by an Imagist", which appeared in 'Poetry; A Magazine of

Verse'. . . . A small group of poets gathered about Mr. Pound,

experimenting along the technical lines suggested, and a cult of

"Imagism" was formed, whose first group-expression was in the little

volume, "Des Imagistes", published in New York in April, 1914. Miss

Lowell did not come actively into the movement until after that time,

but once she had entered it, she became its leader, and it was chiefly

through her effort in America that the movement attained so much

prominence and so influenced the trend of poetry for the years

immediately succeeding. Miss Lowell many times, in

admirable articles, stated the principles upon which Imagism is based,

notably

in the Preface to "Some Imagist Poets" and in the Preface to the second

series, in 1916. She also elaborated it much more fully in her volume,

"Tendencies

in Modern American Poetry", 1917, in the articles pertaining to the

work

of "H.D." and John Gould Fletcher. In her own creative work, however,

Miss

Lowell did most to establish the possibilities of the Imagistic idea

and

of its modes of presentation, and opened up many interesting avenues of

poetic

form. Her volume, "Can Grande's Castle", is devoted to work in the

medium

which she styled "Polyphonic Prose" and contains some of her finest

work,

particularly "The Bronze Horses".

Lowell, Amy Lawrence (1874-1925), American poet and critic, one of the

leaders of the imagist school (see Imagism). She was born in Brookline,

Massachusetts, and was the sister of astronomer Percival Lowell and

Harvard University President Abbott Lawrence Lowell. She traveled

widely, lectured on poetry, and edited three imagist anthologies. As an

imagist she championed free verse, tight precision in vocabulary, and

concise style. Her volumes of verse include Sword Blades and Poppy

Seeds (1914); Men, Women, and Ghosts (1916), which contains her

well-known poem "Patterns"; Pictures of the Floating World (1919);

What's O'Clock (1925), which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1926; and

Ballads for Sale (1927). Among her critical works are Tendencies in

Modern American Poetry (1917) and the biography John Keats

(1925).

Amy Lowell didn't become a poet until she was years into her

adulthood; then, when she died early, her poetry (and life) were nearly

forgotten -- until gender studies as a discipline began to look at

women like Lowell as illustrative of an earlier lesbianism. She

lived her later years in a "Boston marriage" and wrote erotic love

poems addressed to a woman.

T. S. Eliot called her the "demon saleswoman of poetry." Of

herself, she said, "God made me a businesswoman and I made myself a

poet."

Amy Lowell was born to wealth and prominence. Her paternal grandfather,

John Amory Lowell, developed the cotton industry of Massachusetts with

her maternal grandfather, Abbott Lawrence. The towns of Lowell

and

Lawrence, Massachusetts, are named for the families. John Amory

Lowell's

cousin was the poet James Russell Lowell.

Amy was the youngest child of five. Her eldest brother, Percival

Lowell, became an astronomer in his late 30s and founded Lowell

Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona. He discovered the "canals" of

Mars. Earlier he'd written two books inspired by his travels to

Japan and the Far East. Amy Lowell's other brother, Abbott Lawrence

Lowell, became president of Harvard University.

The family home was called "Sevenels" for the "Seven L's" or Lowells.

Amy Lawrence was educated there by an English governess until 1883,

when she was sent to a series of private schools. She was far

from a model student. During vacations, she traveled with her family to

Europe and

to America's west.

In 1891, as a proper young lady from a wealthy family, she had her

debut. She was invited to numerous parties, but did not get the

marriage proposal that the year was supposed to produce. A university

education was out of the question for a Lowell daughter, although not

for the sons. So Amy Lowell set about educating herself, reading

from the 7,000 volume library of her father and also taking advantage

of the Boston Athenaeum.

Mostly she lived the life of a wealthy socialite. She began a lifelong

habit of book collecting. She accepted a marriage proposal, but the

young man changed his mind and set his heart on another woman.

Amy Lowell went to Europe and Egypt in 1897-98 to recover, living on a

severe diet that was supposed to improve her health (and help with her

increasing weight problem). Instead, the diet nearly ruined her health.

In 1900, after her parents had both died, she bought the family home,

Sevenels. Her life as a socialite continued, with parties and

entertaining. She also took up the civic involvement of her father,

especially in supporting education and libraries.

Amy had enjoyed writing, but her efforts at writing plays didn't meet

with her own satisfaction. She was fascinated by the theater. In

1893 and 1896, she had seen performances by the actress Eleanora

Duse. In 1902, after seeing Duse on another tour, Amy went home

and wrote a tribute to her in blank verse -- and, as she later said, "I

found out where my

true function lay." She became a poet -- or, as she also later

said,

"made myself a poet."

By 1910, her first poem was published in Atlantic Monthly, and three

others were accepted there for publication. In 1912 -- a year that also

saw the first books published by Robert Frost and Edna St. Vincent

Millay -- she published her first collection of poetry, A Dome of

Many-Coloured Glass.

It was also in 1912 that Amy Lowell met actress Ada Dwyer

Russell. From about 1914 on, Russell, a widow who was 11 years

older than Lowell, became Amy's traveling and living companion and

secretary. They lived together in a "Boston marriage" until Amy's

death. Whether the relationship was platonic or sexual is not

certain -- Ada burned all personal correspondence as executrix for Amy

after her death -- but poems which Amy clearly directed towards Ada are

sometimes erotic and full of suggestive imagery.

In the January 1913 issue of Poetry, Amy read a poem signed by "H.D.,

Imagiste." With a sense of recognition, she decided that she,

too, was an Imagist, and by summer had gone to London to meet Ezra

Pound and other Imagist poets, armed with a letter of introduction from

Poetry editor Harriet Monroe.

She returned to England again the next summer -- this time bringing her

maroon auto and maroon-coated chauffeur, part of her eccentric

persona. She returned to America just as World War I began,

having sent that maroon auto on ahead of her.

She was already by that time feuding with Pound, who termed her version

of Imagism "Amygism." She focused herself on writing poetry in

the new style, and also on promoting and sometimes literally supporting

other poets who were also part of the Imagist movement.

In 1914, she published her second book of poetry, Sword Blades and

Poppy Seeds. Many of the poems were in vers libre (free verse), which

she

renamed "unrhymed cadence." A few were in a form she invented, which

she

called "polyphonic prose."

In 1915, Amy Lowell published an anthology of Imagist verse, followed

by new volumes in 1916 and 1917. Her own lecture tours began in

1915, as she talked of poetry and also read her own works. She

was

a popular speaker, often speaking to overflow crowds. Perhaps the

novelty of the Imagist poetry drew people; perhaps they were drawn to

the

performances in part because she was a Lowell; in part her reputation

for

eccentricities helped bring in the people.

She slept until three in the afternoon and worked through the

night. She was overweight, and a glandular condition was

diagnosed which caused her to continue to gain. (Ezra Pound called her

"hippopoetess.") She was operated on several times for persistent

hernia problems.

She dressed mannishly, in severe suits and men's shirts. She wore

a pince nez and had her hair done -- usually by Ada Russell -- in a

pompadour that added a bit of height to her five feet. She slept on a

custom-made bed with exactly sixteen pillows. She kept sheepdogs

-- at least

until World War I's meat rationing made her give them up -- and had to

give guests towels to put in their laps to protect them from the dogs'

affectionate habits. She draped mirrors and stopped clocks. And,

perhaps most famously, she smoked cigars -- not "big, black" ones as

was

sometimes reported, but small cigars, which she claimed were less

distracting

to her work than cigarettes, because they lasted longer.

In 1915, she also ventured into criticism with Six French Poets,

featuring Symbolist poets little known in America. In 1916, she

published another volume of her own verse, Men, Women and Ghosts. A

book derived from her lectures, Tendencies in Modern American Poetry

followed in 1917, then another poetry collection in 1918, Can Grande's

Castle and Pictures of the Floating World in 1919 and adaptations of

myths and legends in 1921 in Legends.

During an illness in 1922 she wrote and published A Critical Fable --

anonymously. For some months she denied that she'd written it. Her

relative, James Russell Lowell, had published in his generation A Fable

for Critics, witty and pointed verse analyzing poets who were his

contemporaries. Amy Lowell's A Critical Fable likewise skewered

her own poetic contemporaries.

She worked for the next few years on a massive biography of John Keats,

whose works she'd been collecting since 1905. Almost a day-by-day

account of his life, the book also recognized Fanny Brawne for the

first time as a positive influence on him.

This work was taxing on Lowell's health, though. She nearly ruined her

eyesight, and her hernias continued to cause her trouble. In May

of 1925, she was advised to remain in bed with a troublesome hernia. On

May 12 she got out of bed anyway, and was struck with a massive

cerebral hemorrhage. She died hours later.

Ada Russell, her executrix, not only burned all personal

correspondence, as directed by Amy Lowell, but also published three

more volumes of Lowell's poems posthumously. These included some

late sonnets to Eleanora Duse, who had died in 1912 herself, and other

poems considered too controversial for Lowell to publish during her

lifetime. Lowell left her fortune and Sevenels in trust to Ada Russell.

The Imagist movement didn't outlive Amy Lowell for long. Her poems

didn't withstand the test of time well, and while a few of her poems

("Patterns" and "Lilacs" especially) were still studied and

anthologized, she was nearly forgotten.

Then, Lillian Faderman and others rediscovered Amy Lowell as an example

of poets and others whose same-sex relationships had been important to

them in their lives, but who had -- for obvious social reasons -- not

been

explicit and open about those relationships. Faderman and others

re-examined

poems like "Clear, With Light Variable Winds" or "Venus Transiens" or

"Taxi" or "A Lady" and found the theme -- barely concealed -- of the

love of women. "A Decade," which had been written as a

celebration of the ten year anniversary of Ada and Amy's relationship,

and the "Two Speak Together" section of

Pictures of the Floating World was recognized for the love poetry that

it is.

The theme was not completely concealed, of course, especially to those

who knew the couple well. John Livingston Lowes, a friend of Amy

Lowell's, had recognized Ada as the object of one of her poems, and

Lowell wrote back to him, "I am very glad indeed that you liked

'Madonna of the Evening Flowers.' How could so exact a portrait remain

unrecognized?"

And so, too, the portrait of the committed relationship and love of Amy

Lowell and Ada Dwyer Russell was largely unrecognized until recently.

Her "Sisters" -- alluding to the sisterhood that included Lowell,

Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Emily Dickinson -- makes it clear that

Amy Lowell saw herself as part of a continuing tradition of women poets.

Lowell, Robert Traill Spence, Jr. (1917-1977), American poet,

noted for his lyric virtuosity, rich language, and social concern. A

cousin of the distinguished intellectuals Amy Lowell, Percival Lowell,

and Abbott Lowell, Robert Lowell was born in Boston, Massachusetts,

and

educated at Harvard University and Kenyon College. Lowell suffered

religious doubt and temporarily converted to Roman Catholicism in 1940;

later he was imprisoned briefly for refusing to serve in World War II

(1939-1945). During the 1950s he spent time in a mental hospital, and

in the 1960s he took part in the antiwar and civil rights movements.

More Biography:

Robert Lowell was born in 1917 into one of Boston's

oldest and most prominent families. He attended Harvard College for two

years before transferring to Kenyon College, where he studied poetry

under John Crowe Ransom and received an undergraduate degree in 1940.

He took

graduate courses at Louisiana State University where he studied with

Robert

Penn Warren and Cleanth Brooks. His first and second books, Land of

Unlikeness (1944) and Lord Weary's Castle (for which he received a

Pulitzer Prize

in 1946, at the age of thirty), were influenced by his conversion from

Episcopalianism to Catholicism and explored the dark side of America's

Puritan legacy.

Under the influence of Allen Tate and the New Critics, he wrote

rigorously

formal poetry that drew praise for its exceptionally powerful handling

of meter and rhyme. Lowell was politically involved—he became a

conscientious

objector during the Second World War and was imprisoned as a result,

and

actively protested against the war in Vietnam—and his personal life was

full of marital and psychological turmoil. He suffered from severe

episodes

of manic depression, for which he was repeatedly hospitalized.

Partly in response to his frequent breakdowns, and

partly due to the influence of such younger poets as W. D. Snodgrass

and Allen Ginsberg, Lowell in the mid-fifties began to write more

directly from personal experience, and loosened his adherence to

traditional meter and form. The result was a watershed collection, Life

Studies (1959), which forever changed the landscape of modern poetry,

much as Eliot's The Waste Land had three decades before. Considered by

many to be the most important poet in English of the second half of the

twentieth century, Lowell continued to develop his work with sometimes

uneven results, all along defining the restless center of American

poetry, until his sudden death from a heart attack at age 60. Robert

Lowell served as a Chancellor of The Academy of American

Poets from 1962 until his death in 1977.

Lowell's first volume of poems, Land of Unlikeness (1944), reflected

the disturbing effects of World War II. The volume Lord Weary's Castle

(1946; Pulitzer Prize, 1947) contains his highly acclaimed poem

"Colloquy at Black Rock," which centers on a Roman Catholic feast. The

chief long narrative poem in Mills of the Kavanaughs (1951) is a Greek

legend set in New England. Life Studies (1959), which received the

National Book Award in 1960, revealed Lowell's inner torments and

marked him as an influential figure in the emergence of confessional

poetry in the 1950s (see American Literature: 20th-Century Poetry).

Later poems in For the Union Dead (1964) and Near the Ocean (1967) are

more political. His other works of poetry include

Imitations (1961) and The Dolphin (1973; Pulitzer Prize, 1974). Lowell

had

a remarkable ability to express in his poetry both objective and

subjective

views of the turmoil of the contemporary world. His trilogy of plays,

The

Old Glory (1965), is a historical survey of American culture. He also

adapted

the ancient Greek dramas Phaedra (1963) and Prometheus Bound (1969).

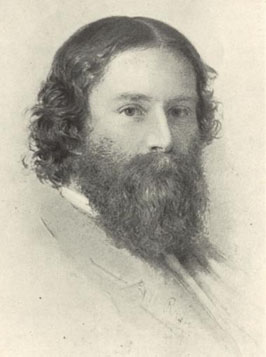

James Russell Lowell, was born

22 February 1819; died 12 August 1891;

American author and diplomat, one of the famous men

of his time but fame and reputation now diminished, was born at Elmwood

in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on the 22nd of February 1819. He was the

son of Charles Lowell, a Unitarian pastor in Boston. On his

mother's

side he was descended from the Spences and Traills, who made their home

in the Orkney Islands, his great-grandfather, Robert Traill, returning

to

England on the breaking out of hostilities in 1775. He was brought up

in

a neighborhood bordering on the open country, and from his earliest

years

he found a companion in nature; he was also early initiated into the

reading

of poetry and romance, hearing Edmund Spenser and Sir Walter Scott in

childhood,

and introduced to old ballads by his mother. He had for schoolmaster an

Englishman

who held by the traditions of English schools, so that before he

entered

Harvard College he had a more familiar acquaintance with Latin verse

than

most of his fellows -- a familiarity which showed itself later in his

mock-pedantic accompaniment to The

Biglow Papers and his macaronic poetry. He was a wide reader,

but a somewhat indifferent student, graduating at Harvard without

special honors in 1838. During his college course he wrote a number of

trivial pieces for a college magazine, and shortly after graduating

printed for private circulation the poem which his class asked him to

write for their graduation festivities.

He was uncertain at first what vocation to choose,

and vacillated between business, the ministry, medicine and law. He

decided at last to practice law, and after a course at the Harvard law

school, was admitted to the bar. While studying for his profession,

however, he contributed poems and prose articles to various magazines.

He cared little for the law, regarding it simply as a distasteful means

of livelihood, yet

his experiments in writing did not encourage him to trust to this for

support.

An unhappy adventure in love deepened his sense of failure, but he

became

betrothed to Maria White in the autumn of 1840, and the next twelve

years

of his life were deeply affected by her influence. She was a poet of

delicate

power, but also possessed a lofty enthusiasm, a high conception of

purity

and justice, and a practical temper which led her to concern herself in

the movements directed against the evils of intemperance and slavery.

Lowell

was already looked upon by his companions as a man marked by wit and

poetic

sentiment; Miss White was admired for her beauty, her character and her

intellectual gifts, and the two became thus the hero and heroine among

a

group of ardent young men and women. The first fruits of this passion

was

a volume of poems, published in 1841, entitled A Year's Life, which was

inscribed by Lowell in a veiled dedication to his future wife, and was

a

record of his new emotions with a backward glance at the preceding

period

of depression and irresolution. The betrothal, moreover, stimulated

Lowell

to new efforts towards self-support, and though nominally maintaining

his

law office, he threw his energy into the establishment, in company with

a friend, Robert Carter, of a literary journal, to which the young men

gave

the name of The Pioneer. It was to open the way to new ideals in

literature

and art, and the writers to whom Lowell turned for assistance --

Hawthorne,

Emerson, Whittier, Poe, Story and Parsons, none of them yet possessed

of

a wide reputation -- indicate the acumen of the editor. Lowell himself

had

already turned his studies in dramatic and early poetic literature to

account

in another magazine, and continued the series in The Pioneer, besides

contributing

poems; but after the issue of three monthly numbers, beginning in

January

1843, the magazine came to an end, partly because of a sudden disaster

which

befell Lowell's eyes, partly through the inexperience of the conductors

and unfortunate business connections.

The venture confirmed Lowell in his bent towards literature. At the

close of 1843 he published a collection of his poems, and a year later

he gathered up certain material which he had printed, sifted and added

to it, and produced Conversations on some of the Old Poets. The

dialogue

form was used merely to secure an undress manner of approach to his

subject; there was no attempt at the dramatic. The book reflects

curiously Lowell's mind at this time, for the conversations relate only

partly to the poets and dramatists of the Elizabethan period; a slight

suggestion sends the

interlocutors off on the discussion of current reforms in church and

state

and society. Literature and reform were dividing the author's mind, and

continued to do so for the next decade. Just as this book appeared

Lowell

and Miss White were married, and spent the winter and early spring of

1845

in Philadelphia. Here, besides continuing his literary contributions to

magazines, Lowell had a regular engagement as an editorial writer on

The

Pennsylvania Freeman, a fortnightly journal devoted to the Anti-Slavery

cause.

In the spring of 1845 the Lowells returned to Cambridge and made their

home

at Elmwood. On the last day of the year their first child, Blanche, was

born,

but she lived only fifteen months. A second daughter, Mabel, was born

six

months after Blanche's death, and lived to survive her father; a third,

Rose,

died an infant. Lowell's mother meanwhile was living, sometimes at

home,

sometimes at a neighboring hospital, with clouded mind, and his wife

was

in frail health. These troubles and a narrow income conspired to make

Lowell

almost a recluse in these days, but from the retirement of Elmwood he

sent

forth writings which show how large an interest he took in affairs. He

contributed

poems to the daily press, called out by the Slavery question; he was,

early

in 1846, a correspondent of the London Daily News, and in the spring of

1848 he formed a connection with the National Anti-Slavery Standard of

New York, by which he agreed to furnish weekly either a poem or a prose

article. The poems were most frequently works of art, occasionally they

were tracts;

but the prose was almost exclusively concerned with the public men and

questions of the day, and forms a series of incisive, witty and

sometimes

prophetic diatribes. It was a period with him of great mental activity,

and is represented by four of his books which stand as admirable

witnesses

to the Lowell of 1848, namely, the second series of Poems, containing

among others "Columbus", "An Indian Summer Reverie", "To the

Dandelion",

"The Changeling"; A Fable for Critics, in which, after the manner of

Leigh

Hunt's The Feast of the Poets, he characterizes in witty verse and with

good-natured satire American contemporary writers, and in which, the

publication

being anonymous, he included himself; The Vision of Sir Launfal, a

romantic

story suggested by the Arthurian legends -- one of his most popular

poems;

and finally The Biglow Papers.

Lowell had acquired a reputation among men of letters and a cultivated

class of readers, but this satire at once brought him a wider fame. The

book was not premeditated; a single poem, called out by the recruiting

for the abhorred Mexican war, couched in rustic phrase and sent to the

Boston Courier, had the inspiriting dash and electrifying rat-tat-tat

of this

new recruiting sergeant in the little army of Anti-Slavery reformers.

Lowell

himself discovered what he had done at the same time that the public

did,

and he followed the poem with eight others either in the Courier or the

Anti-Slavery Standard. He developed four well-defined characters in the

process -- a

country farmer, Ezekiel Biglow, and his son Hosea; the Rev. Homer

Wilbur,

a shrewd old-fashioned country minister; and Birdofredum Sawin, a

Northern

renegade who enters the army, together with one or two subordinate

characters;

and his stinging satire and sly humour are so set forth in the

vernacular

of New England as to give at once a historic dignity to this form of

speech. (Later he wrote an elaborate paper to show the survival in New

England

of the English of the early 17th century.) He embroidered his verse

with

an entertaining apparatus of notes and mock criticism. Even his index

was

spiced with wit. The book, a caustic arraignment of the course taken in

connection with the annexation of Texas and the war with Mexico, made a

strong impression, and the political philosophy secreted in its lines

became

a part of household literature. It is curious to observe how repeatedly

this arsenal was drawn upon in the discussions in America about the

"Imperialistic"

developments of 1900. The death of Lowell's mother, and the fragility

of his wife's health, led Lowell, with his wife, their daughter Mabel

and

their infant son Walter, to go to Europe in 1851, and they went direct

to Italy. The early months of their stay were saddened by the death of

Walter in Rome, and by the news of the illness of Lowell's father, who

had a slight shock of paralysis. They returned in November 1852, and

Lowell

published some recollections of his journey in the magazines,

collecting

the sketches later in a prose volume, Fireside Travels. He took some

part

also in the editing of an American edition of the British Poets, but

the

low state of his wife's health kept him in an uneasy condition, and

when

her death (27th October 1853) released him from the strain of anxiety,

there

came with the grief a readjustment of his nature and a new intellectual

activity.

At the invitation of his cousin, he delivered a course of lectures on

English

poets before the Lowell Institute in Boston in the winter of 1855. This

first formal appearance as a critic and historian of literature at once

gave him a new standing in the community, and was the occasion of his

election

to the Smith Professorship of Modern Languages in Harvard College, then

vacant by the retirement of Longfellow. Lowell accepted the

appointment, with the proviso that he should have a year of study

abroad. He spent his time mainly in Germany, visiting Italy, and

increasing his acquaintance with

the French, German, Italian and Spanish tongues. He returned to America

in the summer of 1856, and entered upon his college duties, retaining

his position for twenty years. As a teacher he proved himself a

quickener of thought

amongst students, rather than a close and special instructor. His power

lay

in the interpretation of literature rather than in linguistic study,

and

his influence over his pupils was exercised by his own fireside as well

as in the relation, always friendly and familiar, which he held to them

in the classroom. In 1856 he married Frances Dunlap, a lady who had

since

his wife's death had charge of his daughter Mabel.

In the autumn of 1857 The Atlantic Monthly was established, and Lowell

was its first editor. He at once gave the magazine the stamp of high

literature and of bold speech on public affairs. He held this position

only until the spring of 1861, but he continued to make the magazine

the vehicle of his poetry and of some prose for the rest of his life;

his prose, however, was more abundantly presented in the pages of The

North American Review during the years 1862-72, when he was associated

with Charles Eliot Norton in its conduct. This magazine especially gave

him the opportunity of expression of political views during the

eventful years of the War of the Union. It was in The Atlantic during

the same period that he published a second series of The Biglow Papers.

Both his collegiate and editorial duties stimulated his critical

powers, and the publication in the two magazines, followed by

republication in book form, of a series of studies of great authors,

gave him an important place as a critic. Shakespeare, Dryden, Lessing,

Rousseau, Dante, Spenser, Wordsworth, Milton, Keats, Carlyle, Thoreau,

Swinburne, Chaucer, Emerson, Pope, Gray -- these are the principal

subjects of his prose, and the range of topics indicates the

catholicity of his taste. He wrote also a number of essays, such as "My

Garden Acquaintance", "A Good Word for Winter", "On a Certain

Condescension in Foreigners", which were incursions into the field of

nature and society. Although the great bulk of his writing was now in

prose, he made after this date some of his most notable ventures in

poetry. In 1868 he issued the next collection in Under the Willows and

other Poems, but in 1865 he had delivered his "Ode recited at the

Harvard Commemoration", and the successive centennial historical

anniversaries drew from him a series of stately odes.

In 1877 Lowell, who had mingled so little in party politics that the

sole public office he had held was the nominal one of elector in the

Presidential election of 1876, was appointed by President Rutherford B.

Hayes minister resident at the court of Spain. He had a good knowledge

of Spanish language and literature, and his long-continued studies in

history and his quick judgment enabled him speedily to adjust himself

to these new relations. Some of his despatches to the home government

were published in a posthumous volume, Impressions of Spain. In 1880 he

was transferred to London as American minister, and remained there

until the close of President Chester A. Arthur's administration in the

spring of 1885. As a man of letters he was already well known in

England, and he was in much demand as an orator on public occasions,

especially of a literary nature; but he also proved himself a sagacious

publicist, and made himself a wise interpreter of each country to the

other.

Shortly after his retirement from public life he published Democracy

and

other Addresses, all of which had been delivered in England. The title

address

was an epigrammatic confession of political faith as hopeful as it was

wise

and keen. The close of his stay in England was saddened by the death of

his second wife in 1885. After his return to America he made several

visits

to England. His public life had made him more of a figure in the world;

he was decorated with the highest honors Harvard could pay officially,

and

with degrees of Oxford, Cambridge, St. Andrews, Edinburgh and Bologna.

He

issued another collection of his poems, Heartscase and Rue, in 1888,

and

occupied himself with revising and rearranging his works, which were

published

in ten volumes in 1890. The last months of his life were attended by

illness,

and he died at Elmwood on the 12th of August 1891. After his death his

literary

executor, Charles Eliot Norton, published a brief collection of his

poems,

and two volumes of added prose, besides editing his letters.

The spontaneity of Lowell's nature is delightfully disclosed in his

personal letters. They are often brilliant, and sometimes very

penetrating in their judgment of men and books; but the most constant

element is a

pervasive humor, and this humor, by turns playful and sentimental, is

largely

characteristic of his poetry, which sprang from a genial temper, quick

in its sympathy with nature and humanity. The literary refinement which

marks his essays in prose is not conspicuous in his verse, which is of

a

more simple character. There was an apparent conflict in him of the

critic

and the creator, but the conflict was superficial. The man behind both

critical

and creative work was so genuine, that through his writings and speech

and

action he impressed himself deeply upon his generation in America,

especially

upon the thoughtful and scholarly class who looked upon him as

especially

their representative. This is not to say that he was a man of narrow

sympathies. On the contrary, he was democratic in his thought, and

outspoken in his rebuke of whatever seemed to him antagonistic to the

highest freedom. Thus, without taking a very active part in political

life, he was recognized as one of the leaders of independent political

thought. He found expression in so many ways, and was apparently so

inexhaustible in his resources, that his very versatility and the ease

with which he gave expression to his thought sometimes stood in the way

of a recognition of his large, simple political ideality and the

singleness of his moral sight.

Father: Charles Lowell (Unitarian pastor, b. 1782, d. 1861)

Wife: Maria White (three daughters, one son, d. 27-Oct-1853)

Daughter: Blanche (d. after fifteen months)

Daughter: Mabel

Daughter: Rose (d. infancy)

Son: Walter (d. infancy, in Rome)

Wife: Frances Dunlap (m. 1856, d. 1885)

University: Harvard University (1838)

US Ambassador to the United Kingdom 1880-85

Atlantic Monthly Editor, 1857-61

See link for sample of Biglow

Papers

See link for Ode to Harvard Men,

who died in the Civil War

Sources:

Bigelow Family Genealogy Volume. I page.350;

Howe, Bigelow Family of America;

Microsoft(R) Encarta(R) 96 Encyclopedia. (c) 1993-1995

Who Was Who in America, published 1963;

Who Was Who in America, Fifth Printing;

Scribners Sons, Dictionary of America Biography, Supplement 3,

published 1973.

Modified - 12/09/2013

(c) Copyright 2013 Bigelow Society, Inc. All rights

reserved.

Rod Bigelow - Director

< rodbigelow@netzero.net >

Rod Bigelow (Roger Jon12 BIGELOW)

Box 13 Chazy Lake

Dannemora, N.Y. 12929

<

rodbigelow@netzero.net >

<

rodbigelow@netzero.net >

BACK TO THE BIGELOW

SOCIETY PAGE

BACK TO BIGELOW HOME PAGE