Lyon Mountain..

The Town That Refuses to Die...

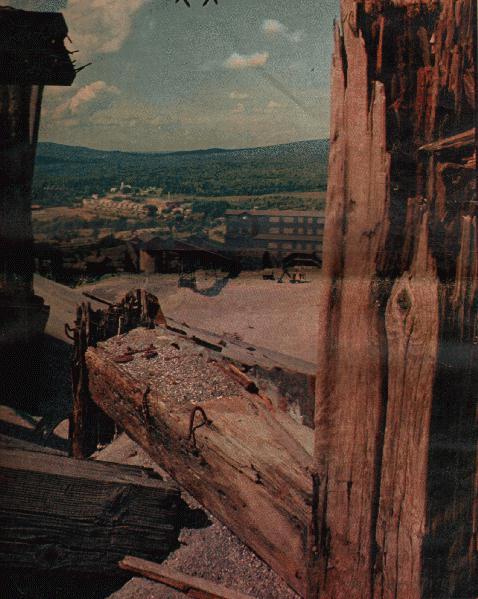

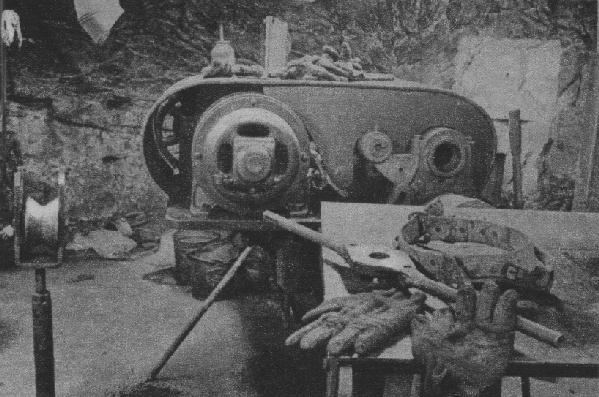

[empire1.jpg]

Photo 1967 by Dick Bandy..from article

in Empire magazine Nov. 5, 1967.

The photo above represents a dying town and

business (mining iron ore), by framing present day (1967) Lyon Mountain

with decaying wooden timbers of old mining operation. The following article

is from a 1967 point of view, and reflects the fears and hopes of the residents

of Lyon Mountain just after this final mine closing.....ROD

Lyon Mt. Fights to Survive

"The story you are about to read is the

story of a little mining village called Lyon Mountain, in the Town of

Dannemora, located in the Adirondack Mountains of New York State."

[empire1.jpg]

Photo 1967 by Dick Bandy..from article

in Empire magazine Nov. 5, 1967.

The photo above represents a dying town and

business (mining iron ore), by framing present day (1967) Lyon Mountain

with decaying wooden timbers of old mining operation. The following article

is from a 1967 point of view, and reflects the fears and hopes of the residents

of Lyon Mountain just after this final mine closing.....ROD

Lyon Mt. Fights to Survive

"The story you are about to read is the

story of a little mining village called Lyon Mountain, in the Town of

Dannemora, located in the Adirondack Mountains of New York State."

The letter started with that paragraph. It was

written to President Johnson, and it was the last resort of a village in

the terminal stages of a disease called unemployment.

On June 30 the mine shut down. It was no longer

economically feasible to run it, representatives of Republic Steel 'told

the people of Lyon Mountain. Like a patient the doctor has pronounced incurable,

the little village, with over 250 men out of

work, shuddered, spent days in shock, then, finally, squared its shoulders

and refused to accept the verdict.

John Kaska made 18 cents an hour when he first

went to work in the mines in 1924. He was 15 years old. When his

father, also a miner, died, John accepted the obligation to help support

the family. John Kaska's son did not become a miner.

"I wouldn't let him go to the mine," Kaska says now. "It's no job for a

young man".

Most young men of Lyon Mountain did go to work

for the mine, though. Of the 1,300 population, almost every person was dependent

in some way on the mine. Now many of them agree with school principal Bernard

Harrica, who has lived and

worked in Lyon Mountain for more than 20 years, that the village was

conquered finally by "the age of bigness."

Since the discovery by a trapper in 1823

of a fine grade of iron ore on the site, there has been mining near the little

village. In 1873 the Chateaugay Iron Co. bought mineral rights and began building

and mining. Men came to work for Chateaugay -brought their families to live

in Lyon Mountain-men who were the finest hard-rock miners in the world,"

according

to Harrica.

With hammers and hand-held drills they attacked

the layers beneath the earth and brought down great slabs of "muck"

for the "crushers." The monstrous teeth of the crushers broke the muck into

smaller and smaller particles until it could be

whirled on a giant magnet. The iron ore clung to the magnet, the sand, or

"tailings," flew off. The ore was loaded on wagons,

drawn by teams of horses to Chazy Lake where it was forged into ingots of

pig iron. The pig iron went by Chateaugay Railroad cars, later the Delaware

and Hudson Line, to a blast furnace and, from there, all over the world.

The cables of the Golden Gate Bridge are made with steel from Chateaugay

ore.

Back at Lyon Mountain the process continued without

interruption. Methods changed, the mine itself burrowed deeper and deeper,

from its original 600 feet to 2,313 feet. Level after level was carved beneath

the earth, 18 of them all together. A generation was born, grew up, worked

in the mine, and died. Another generation took its place. If a man's father

was a plumber in the mine, he became a plumber. A man might follow his father

into the sintering mill where the ore was separated from the aggregate, cooked

over oil flames until red hot, sprayed with cold water, and dumped as sintered

ore ready to make

Chateaugay pig iron. If the father was an electrician, a "developer, a stope

man," a carpenter, chances were the son followed

on the same job.

The village was simply an extension of the mine.

Chateaugay owned the houses, the fire department, the water company,

the stores. If a child grew ill, the company doctor was called; if a light

bulb burned out in the kitchen, the company supplied a new one. Rents on the

duplex houses averaged little more than $11 a month.

The houses were not beautiful. It was as though,

surrounded by the breathtaking beauty of the Adirondack Mountains, the

people of the village didn't look for beauty any closer to home.

They were a practical people, not afraid of work.

On Belmont street they built a school out of concrete blocks made in their

own town. They filled a bog with ore sand and built an athletic field on it.

All the while another mountain was growing at their

back door. The shadow of its dark, treeless slopes loomed above the

village. Dust from the black mountain covered clothes hanging on the line,

children's bare feet, and window sills in summer. It was a mountain of ore

tailings, sterile sand where nothing grows. Brought from the heart of the

earth, it dominated the village.

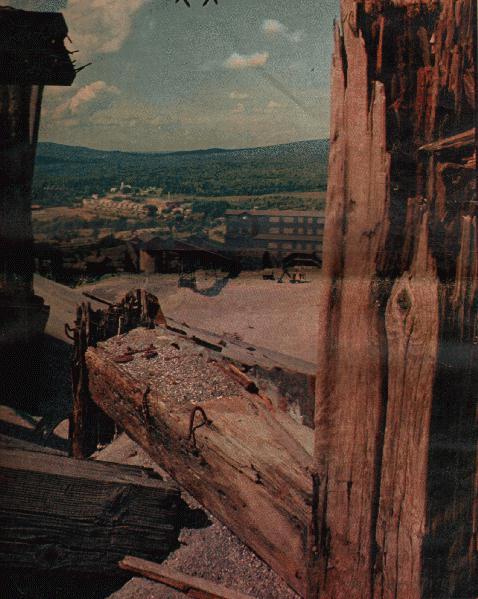

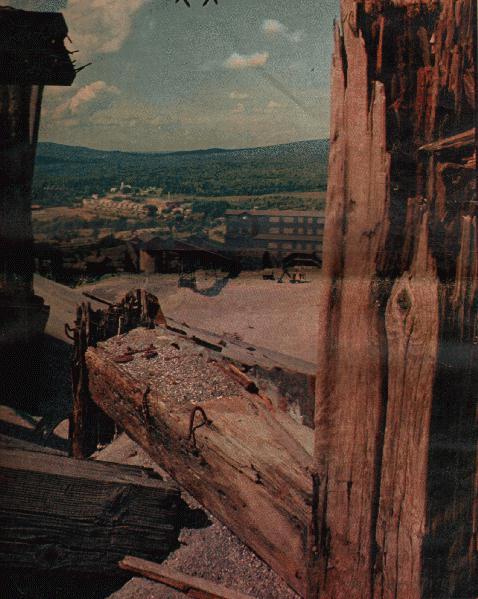

[silentm.jpg]

A silent mine and a mountain of black ore sand dominate

the Adirondack village of Lyon Mountain,

where 250 men lost their jobs in a mine shutdown on June 30,

1967.

William LaMountain looked up at the brooding pile

of black sand every day for 55 years and 10 months as he went to work in

the mine. His father had worked for the railroad hauling away ore, but William

chose to "go down in the mine." He

[silentm.jpg]

A silent mine and a mountain of black ore sand dominate

the Adirondack village of Lyon Mountain,

where 250 men lost their jobs in a mine shutdown on June 30,

1967.

William LaMountain looked up at the brooding pile

of black sand every day for 55 years and 10 months as he went to work in

the mine. His father had worked for the railroad hauling away ore, but William

chose to "go down in the mine." He

started when drilling was done with hammers, and he stayed until he had

seen five of his 10 children also working in the mine. Now that the mine

is closed he is drawing retirement pay. His sons have gone to work on other

jobs. The black mountain still looms.

Ten years ago (1957) the mining company sold most

of the houses. The people living in them bought them at bargain prices on

10, 15, and 20-year mortgages. Now the people don't want to leave those houses.

They don't want to leave Lyon Mountain. Probably 90 per cent of them are second

and third generation residents, far removed from their Polish, Italian, Irish,

Spanish, Swedish, and French ancestry. They even have an accent, distinctly

their own, with tinges or Irish, Swedish, and some indefinable blend.

Even the young people don't want to leave. Today

they work in construction and they buy new cars and they move to Plattsburgh

or to Buffalo or to Toronto and the old folks say "give my love to John or

Dick or Sam - if you see him." The next

thing you know they're back. Their roots are as deep as the ore of the Chateaugay

mine.

The school population was 410 before the mines

closed. Today it is 399. It's a good school, principal Harrica says. Fifty

per cent of the graduates go to college. He estimates the mine closing has

caused him to lose only six children.

The bowling team is a bit short but eager groups

of Boy Scouts, Girl Scouts, and Brownies still are hiking. On hot summer days

the swimming pool was still full of splashing youngsters. The school soccer,

basketball, baseball, and public speaking teams still are competing. The

social studies club is active. The dramatics enthusiasts still sponsor a

one-act play festival. The ski club is looking forward to a snowy winter.

The skating rink is ready. The hunting and fishing and trapping are just as

good as before the mine closed.

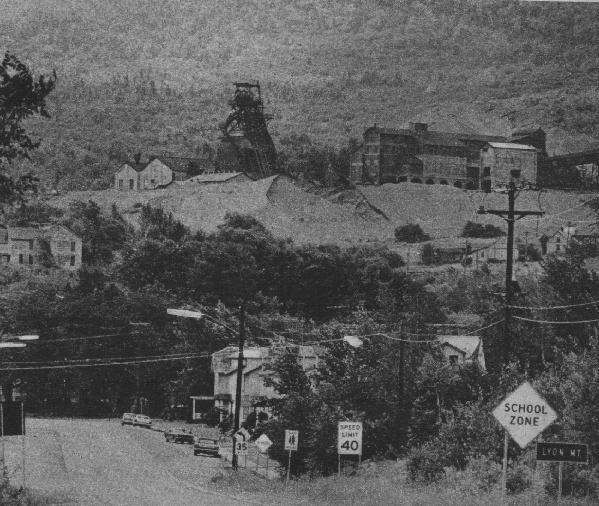

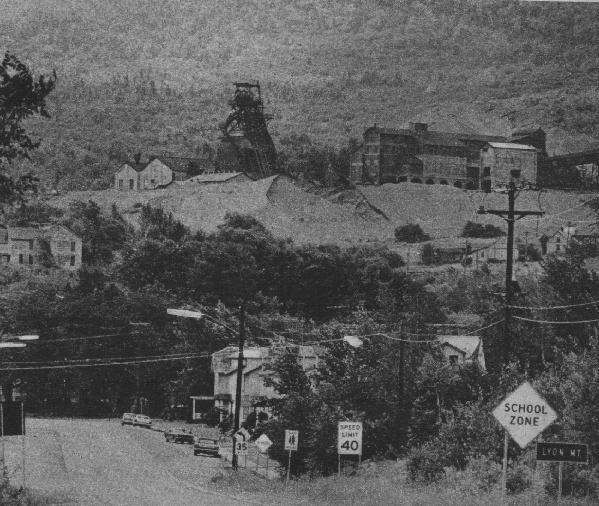

[mutevid.jpg]

Mute evidence of the last day. Worn gloves stiff with Chateaugay

"muck", dropped where the workman finished.

Anyway, the people of Lyon Mountain have known

mine closings before. In years past, when work was slow or the ore

[mutevid.jpg]

Mute evidence of the last day. Worn gloves stiff with Chateaugay

"muck", dropped where the workman finished.

Anyway, the people of Lyon Mountain have known

mine closings before. In years past, when work was slow or the ore

market down, they ezperienced temporary shutdowns. They have not yet really

felt the economic impact of this one, Harrica

says. Right now nobody is hungry. Morale is good. There are only two families

supported by welfare. Of course, the men go

a long way to work. They work in Dannemora or Mineville or drive the 30

miles to Plattsburgh. It's not too bad in the summer,

but most of them express dread of the long drive in winter.

A salvage operation.which will take about two years

employs 65 village men at the mine. Clifford Ducharme, whose father

and grandfather were minem1supervises the underground salvage operation

for Wayne ToIhert's Consolidated Contracting Corp. of Buffalo. Ducharme has

spent so much time down in the mine that he figures by now it is his "natural

habitat." The workmen are salvaging copper tubing, pumps and ventilators,

and the giant machinery of mining. Through the long "drifts" that

wander east and west around the village they seek out salvageable material

and find ways to get it up to the surface using the narrow shafts, an "ore

skip" and a "man skip."

Other villagers, in the meantime, are concerned

with salvaging the village itself. Mr. and Mrs. Clarence Lawrence are acutely

aware of the problem which hovers, like the black mountain, over the village.

Lawrece went to work in the mines at the age of 17 after his father had been

seriously injured at the same work. Mrs. Lawrence is from a mining family

and has lived in Lyon Mountain all her life.

With other residents this couple formed the Lyon

Mountain Citzens' Committee for Industrial Development. It was Mrs. Lawrence

who wrote the letter quoted at the beginning of this story.

As a result of the letter, copies of which went

to Gov. Rockefeller, Senators Javits and Kennedy, Rep. Carlton King,

State Sen. Ronald Stafford, and Assemblyman Louis Wolfe, the committee was

advised to get in touch with specific agencies.

They have, since, written letters and held meetings. They have met with

state and federal government agents, with representatives of the Federal

Economic Development Agency, of the State Department of Commerce, and with

their own town supervisor and councilmen.

"The people of Lyon Mountain are skilled enough

to build a town by themselves," Clarence Lawrence says. "In this village

there are plumbers, carpenters, electricians, surveyors, engineers, men

with every skill needed to build an entire town." "The town has two major

assets," Bernard Harrica says, "the mine and skilled men, a labor pool of

250 trained craftsmen."

"Add to that," he says, "abundant electric power,

attractive recreational facilities, good schools and highways, and you can

see the potential of the town. All we need are industries to use that potential."

"The dam and water sources have been turned over

to the Town of Dannemora by Republic Steel," Donald Breyette, town

supervisor, says. "The company also will turn over five mine buildings unless

the mine and sintering mill are sold to another

company. The buildings are the mill office, the power house, the machine

shop, the change house, and the hoist building. Also

according to Breyette, the town has been offered the ore sand pile, good

for making cement, and 25 to 30 acres of land.

In the meantime, the village must elect water and

sewer commissioners. It must continue operating the fire department which

villagers voluntarily took over when the mining company left. It must face

the fact of taxes to run an unincorporated village or hamlet. It must shake

off the lethargy left over from a paternalistic company. But first it must

find an industry or industries to employ its men in the village where they

live.

At the American Legion coffee shop we talked with

some of the men. They have time to talk now. They're not going anywhere.

Anthony Kwetcian spent 29 years in the mine. He was a developer, opening

up new stopes, squirming up the "raises" that connected two levels below

ground so that, later, the "stope men" could come in and make the "muck."

The drillers prepared the rock with spaced holes, sometimes working three

or more miles from the main center of the level, in "drifts," or

long tunnels which wander away like crooked spokes of a wheel.

William Pinko was 33 years in the mine, as

developer and stope man. When the stope man finished with the muck the

chute pullers took over to get it to the ore pass. Cletus Benjamin was a

scraper, scraping muck to the chute down which it

dropped to the crusher.

We had stirred memories in the men. We left them

swapping yarns, their unique accent coloring the special language of mining.

Kwetcian was telling them about the time he broke his leg and had to be taken

out of the raise with a "tuggerbox," a

small portable hoist with a tub attached.

The company required every employe to learn carpentry,

plumbing, and general maintenance before training for a specific

job. The men at the American Legion hall were skilled, experienced craftsmen

who could work at any of a dozen trades.

The village is quiet during school hours. There

are only houses, no offices, few stores. Besides the American Legion coffee

shop and bar there is Bernard Chase's service station a bar and grill, and

a liquor store. The men tell us the first thing to be built in a mining town

is a bar and the second thing is a jail. We found the old jail, long unused.

Lawrence remembers the last man incarcerated there. The prisoner stayed overnight,

long enough to get sober and hungry, and Lawrence's mother scrambled some

eggs for him.

There are two churches in the village, a Catholic

church for the 95 per cent of the villagers who are Catholic, and a Methodist

church for the rest.

The only doctor in town has retired. There is no

dentist. The dental hygienist at school cares for the children as well as

she can. A well child clinic is sponsored by the P.T.A. Emergencies and serious

health problems must go to Dannemora.

There are still active organizations. These have

been helping the citizens' committee collect money to place a one-page advertisement

in a financial magazine. They hope to attract industry to their town with

the ad. They have raised almost enough

money. The W.S.C.S., the Catholic Daughters, the American Legion and auxiliary,

the volunteer firemen and auxiliary, the

Confraternity of Christian Doctrine Teachers, the United Steel Workers local

all have joined in the fight which Lyon Mountain

is waging, the fight to live.

Article by Jean Rausch

Photos by Dick Bandy

More pictures from this article can be found on following pages:

page 2

page 3

page 4

Rod Bigelow

Box 13 Chazy Lake

Rod Bigelow

Box 13 Chazy Lake

Dannemora, N.Y. 12929

rodbigelow@netzero.net

rodbigelow@netzero.net  Back to History Page

Back to History Page

BACK TO BIGELOW HOME PAGE

BACK TO BIGELOW HOME PAGE